The book edited by Francesco Monico and published by Marsilio Editori is titled "Spiritualità", and it contains the results of the dialogue between Michelangelo Pistoletto and Father Antonio Spadaro on universal subjects such as art, religion, but also technology and artificial intelligence. It is precisely with these topics that we started our conversation with the artist

“Spiritualità was born from a profound and unexpected dialogue between Michelangelo Pistoletto and Antonio Spadaro. Two men with seemingly distant paths, but united by the desire to explore the connections between art, philosophy, science and spirituality. Their conversations did not take place in an institutional context, but in a neutral space, without pre-established affiliations: around a table, sharing meals and dinners, with Spadaro as a guest at the artist’s home”. Through these words Francesco Monico guides readers into the heart of a conversation that sees a give and take between the voice of one of the most famous Italian artists and that of the undersecretary of the Vatican Dicastery for Culture and Education. We were inspired by the many reflections included in the volume to give shape to our dialogue with Michelangelo Pistoletto.

During your conversation with Antonio Spadaro, you stated: “I live on feeling, don’t you see that I am full of feeling? But it is the feeling of reason”. As an artist and as a human being, how have you structured your relationship with feeling and reason?

I believe that all of this comes from a basic need: to understand something of what happens to us because we exist. This basic lack – related to self-knowledge – means that, as soon as an answer to this need for knowledge emerges, a feeling is created. Feeling for me is seeing that there are answers to imprecise questions. As I became an adult, I felt the question grow within me regarding the reason for existence, but all of humanity wants awareness and knowledge of itself. The need to know is not only an individual phenomenon, but a common, collective one. That is why, at a certain point, religion becomes necessary – the word religion comes from religare, to unite: it binds, unites people in this need to know and recognize themselves as part of a humanity made up of many beings, all with the same root. Every time there is the conquest of a sense of life deriving from some kind of response – which does not necessarily have to be totally rational –, this response creates a feeling. Something happens that is wonderfully responsive to these basic needs.

Speaking of religion, you said: “Religion is the bank where we put the most precious asset we have, that is, life”. What kind of bank is religion in this historical moment, in your opinion?

Religion is a part of life, not only on a mental level, but on a practical level, because the economy, whether practical or intellectual, determines how we live together. The economy means always having the ability to survive thanks to our activity, our work, our understanding with other members of society. Nowadays we find ourselves faced with very conflicting interests, due to phenomena of both religious and political origin. Each type of religion has its own “clientele”, which is part of a political and economic system, not just a conceptual or spiritual one. Therefore, spirituality is deeply connected to everyday life. When I speak of a bank, I am alluding to something that forms the basis of an idea of ownership, just like there are religions that own different banks, which not only compete with each other, but wage war to possess a patrimony that occupies the dimension of money and its use. We have reached the point of unscrupulous use of the financial phenomenon, which has even become a religious phenomenology. The more powerful you are economically, the more you are thought of as divine.

When you talk about religion you also use other very concrete terms, such as “responsibility”, a key topic of your artistic research. In fact you said: “It is not about waiting for divine judgment, but about taking on the responsibility of judging ourselves, here and now, between the heaven and the hell we have built”. What can we do, today, as humanity, as a community, to think that the future is still a possibility?

What is needed is a reversal of the trend in the field of practical life. The human capacity to create takes on a very precise responsibility, which can be in favour of war or against it. Peace is a phenomenon that human beings can create, it is not something that happens like everything else in the making of real, planetary, physical life. Physical life happens via nature’s continuous consumption of itself. Nature eats itself, feeds itself and kills itself to live. But, artifice, which is a human ability, can allow us to live, feed ourselves and coexist without the need to eat human beings. Those who wage war do so by killing people, feeding on them for their own system of power. We have to change the mental register: eliminate the phenomenon of feeding off the killing of others. This is the only conquest that humanity can make today to set itself apart from monstrosity and wickedness – phenomena that are equally human. Human beings must no longer feed on human beings –, which is something very different from the animal that feeds on another animal in nature or from the cow that feeds on grass. Human beings must not only find a balance with nature, but within the concept of what is human. We talk about sustainability, but we are destroying the natural world, the existing world, out of hunger for power. In destroying nature, we are practically and culturally destroying the human race. We are cultural cannibals. Art must bring an end to this cannibalism and the first companion that art can find in this enterprise is religion, to unite, to re-bond. We at Cittadellarte are laying out, through education, a practical path towards this dimension. Working with religious figures, who gain this awareness, is fundamental for the artist. Art has as its first collaborators the bankers of religion.

You also refer to art as the “root of thought”.

Arte Povera was born out of this need for essentiality, for the elimination of the superfluous. There is a fundamental phenomenology to consider, that of the root, of radicality. A seed placed in the earth splits open, and from this division a new tree is born. In nature we find the phenomenology of life that continuously reproduces itself beginning from a seed.

All this is connected to the idea of fermentation that you spoke about in the dialogue with Spadaro.

The seed does not remain intact, it alters. Life occurs because the seed creates a duality in itself, dividing into two parts that affect each other to the point of creating this continuous fermentation in nature. We too, with thought and actions, create this fermentation, knowing that from any type of encounter a third element is always born, as evidenced by the formula of creation, which I drew from the mathematical sign for infinity, where there is infinity, but the finite is missing. The finite occurs by crossing the same line twice: between the two circles of infinity a third circle is born, of the finite. In the two external circles a continuous fermentation occurs and in the central circle a new element is born, which did not exist. With this symbol one can create monsters, conflict, but the two elements can also combine to create a dynamic harmony. Today the formula exists: either we continue using it to make war or we use it to make peace.

Within this context, technology, in your opinion, is a useful means to “go directly from the potential to the actual” and artificial intelligence “is a tool to elevate humanity, to build a more equitable and sustainable future” as part of an “algorithmic spirituality”. As an artist, how do you use these tools and what use do you hope humanity will make of them, not to build monsters but opportunities to engage, to relate?

Nature created this universe, which is much more extensive than we can imagine. There is a unifying principle, that of the union between space-time and mass-energy. This duality exists in the calculation possibilities that we use with algorithms, where we have a concept almost of pre-universal absence and of a universal presence that answer the question: where does the universe come from? The universe comes from the void and proceeds and extends out into the void. The void can be thought of as zero, one is the physical that develops from within this zero. Zero is not nothingness, it is the void. In my Quadro specchiante the mirror has no image of its own, it is totally empty, and that is why it can allow itself to host all possible images in existence. It is zero representation, but it becomes infinite representation because it collects the infinity of existence. In my Quadro specchiante there is zero, emptiness, which contains everything. Zero and one is the formula that is used to creatively conceive the universe and this creatively conceived universe is the artificial intelligence that human beings are developing. The power of human beings is to create a universe with the radical ability to put together zero and everything. Everything in existence exists thanks to this combination of duality. 1 plus 1 equals 3, that is the formula that I have identified. Each external circle is a 1, it contains all the existing elements, that duality, meeting in the central circle, gives birth to an element that did not exist, the number 3. The formula is there, we need to figure out if we will use it for destruction or for peace, which also means balance with nature, between man and nature, between artificial intelligence and natural intelligence.

With this conception of emptiness, which you have been carrying forward since the beginning of your artistic career, you questioned the fear of emptiness. And not being afraid, I believe, can be an essential component of the balance you were talking about.

I understand the fear of emptiness. In the case of Alzheimer’s, for example, a void is created between one thought and another, so they are no longer connected. Because of the disease, the void in the human brain is no longer used, as it should be, to unite the separate elements, which remain as they are. This fear of emptiness concerns not just the loss of cognition, but also of life. Instead, it is precisely in the void that life is created. A universal void, which is inside the universe, but also outside. Before the birth of the universe there was only emptiness, a generative void, constantly in action.

What was the experience like, for you, of the dialogue with Antonio Spadaro on these issues?

It was very fruitful because on my part there is an openness towards religion and on Spadaro’s part an openness towards art. The text derived from the dialogue is not closed and conclusive, rather, it brings together two continuously different thoughts so that the reader can act as a third circle. The reader comes into play because they find a mental dynamic that includes reasoning. Each reader can have their own vision, which they introduce into the trinamics of this text.

Interview by Arianna Testino

BIO

Michelangelo Pistoletto (1933) is one of Italy’s most famous artists, recognized internationally. His works are present in the collections of the world’s major museums. With the creation in Biella of the Fondazione Pistoletto-Cittadellarte and the Accademia Unidee, he created an active rapport between art and the different parts of the social fabric in order to inspire and produce a responsible transformation of society. In 2003 he was awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Biennale di Venezia. With Marsilio he also published Il Terzo Paradiso [The Third Paradise] (2010).

Captions:

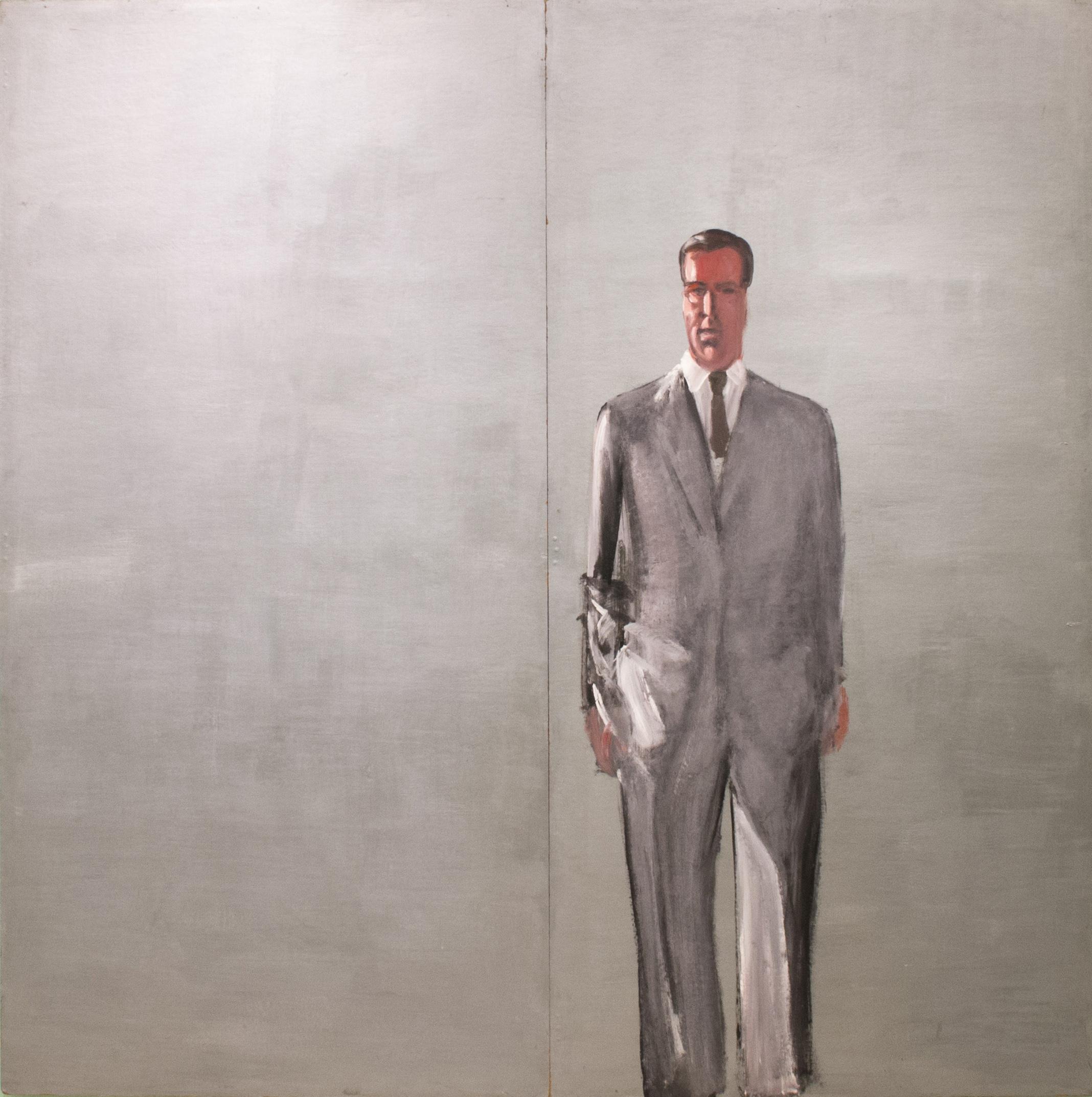

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Autoritratto argento, 1960, oil, acrylic and silver on board, two panels, cm 200 x 200. Fondazione Pistoletto, Biella. Photo Alessandro Lacirasella

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Tre ragazze alla balconata, 1962-1964, painted tissue paper on mirror-polished stainless steel, 200 x 200 cm. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Photo Paolo Bressano

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Metrocubo d’infinito, 1966, mirror and rope, 120 x 120 x 120 cm. Fondazione Pistoletto, Biella. Photo Paolo Pellion

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venere degli stracci, 1967, cast of a classical Venus in cement, rags, mica, 150 x 280 x 100 cm. Artist’s collection, Biella. Photo Paolo Pellion

Michelangelo Pistoletto, L’arte assume la religione, 1977, installation of a mirror on the altar of the Church of San Sicario, 1977. Photograph used as a poster and cover of the catalogue for the exhibition Divisione e moltiplicazione dello specchio – L’arte assume la religione, Galleria Persano, Turin 1978. Photo Paolo Pellion

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Annunciazione Terrae Motus, 1962-1984, silkscreen on mirror-polished stainless steel, two elements, each 250 x 125 cm. Lucio Amelio Collection at the Reggia di Caserta. Photo Courtesy Reggia di Caserta

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Luogo di raccoglimento e di preghiera, 2000, permanent installation. Paoli-Calmettes Oncology Institute, Marseille. Photo M. Spiluttini

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Twentytwo Less Two, 2009, performance and installation, Venice Biennale, 2009, mirror, wood, 22 elements, 300 x 200 cm each. Photo A. Luxem. Courtesy Galleria Continua

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Il Terzo Paradiso nel Bosco di Francesco di Assisi, 2010. A permanent work, inaugurated on September 11, 2010, comprising 121 olive trees located in a walkable area of 3000 square meters within the forest of Francis of Assisi, restored by the FAI. Photo Lucio Lazzara. Courtesy FAI – Fondo Ambientale Italiano

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Codice Trinamico e Formula della Creazione (2021) – Ljubljana, 2022. View of the exhibition Michelangelo Pistoletto – Fourth Generation at the Cukrarna Gallery in Ljubljana. Codice Trinamico (2021), Formula della Creazione (2021), in the center the work Rotolo (1988), exhibited unrolled on this occasion. Photo Alessandro Lacirasella

Michelangelo Pistoletto. Photo Andrea Oitana (cover photo)

Michelangelo Pistoletto, INFINITY. Photo Pierluigi Di Pietro

Related Articles