There is time until 27 July 2025, to visit the exhibition at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice dedicate to the concept of the body in Venetian Renaissance. If you haven’t done so yet, here is our focus with all the interesting details about three works you shouldn’t miss

Curated by Guido Beltramini, Francesca Borgo and Giulio Manieri Elia, the exhibition Corpi moderni. The Making of the Body in Renaissance Venice. Leonardo, Michelangelo, Dürer, Giorgione at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice reveals the many meanings attributed to the human body, spanning art, science, and material culture. If you’re curious and want to learn more, here are the stories of three works ‒ each included in the respective chapters of the exhibition dedicated to anatomy, desire, and the person ‒ featured in the pages of the catalog published by Marsilio Arte.

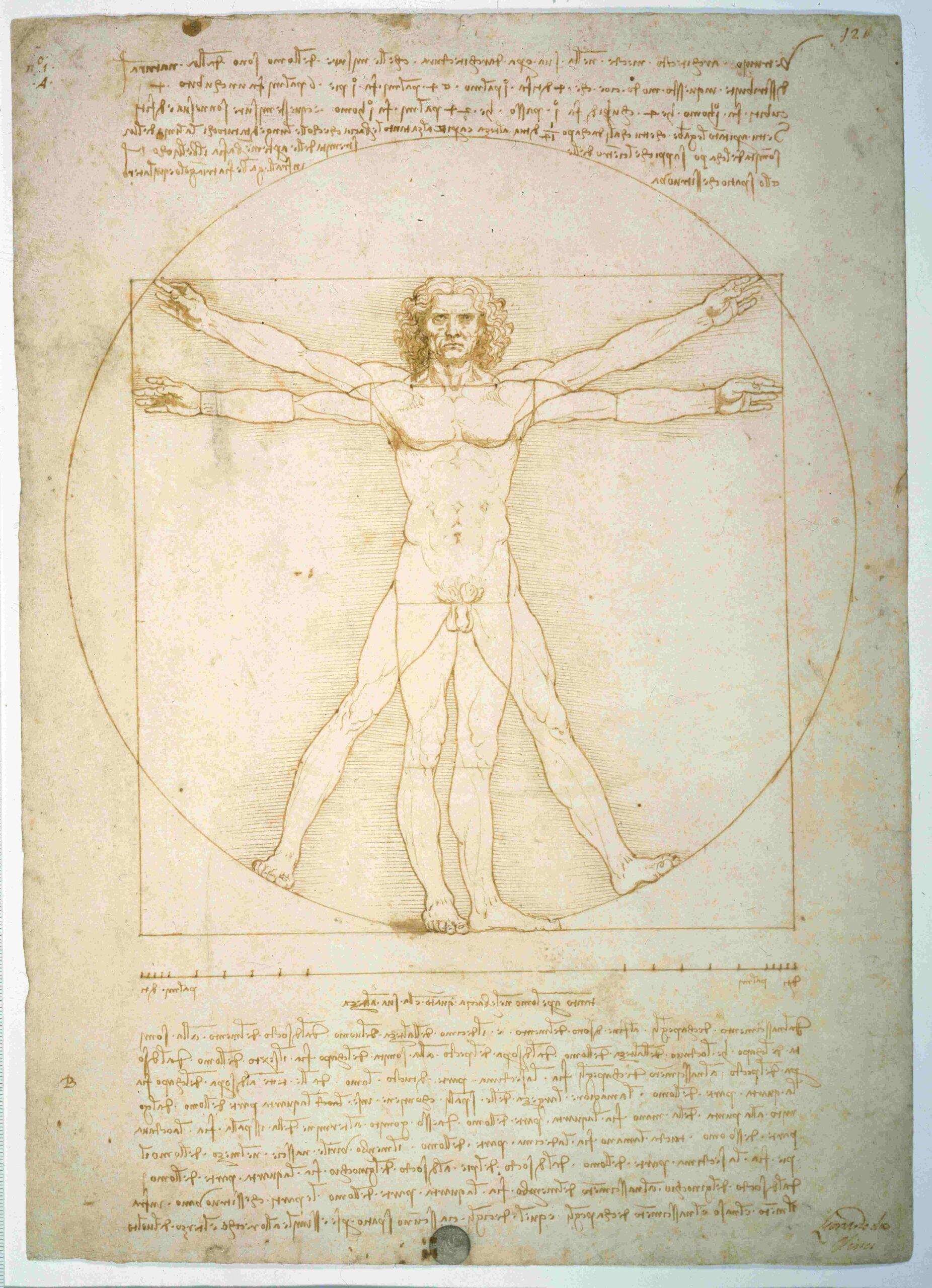

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Proportional Study of the Male Body (Vitruvian Man), 1490-1497, pen and ink on paper, with traces of metal stylus, silver or lead point, brown wash, compass work, 345 x 246 mm. Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia, inv. 228r […]

The drawing, datable between 1490 and 1497, depicts a nude man inscribed within a circle and a square, two geometric figures whose central points are located respectively at the navel and the genitals of the figure. Leonardo begins with a broad campaign of measurement, fundamental for exploring the variability of nature and understanding its rules, which he integrates with the study of ancient and modern canons, such as the one proposed by Leon Battista Alberti in De statua (1450-1464). In this initial, figurative phase of the study, the research remains autonomous from Vitruvius, who is explicitly referenced only in the text, added to the sheet at a later stage, in the space above and below the drawing.

In the figure, the artist diverges from the Vitruvian canon in several points: he divides the height into seven parts instead of six, tilts the left foot to maintain proportional consistency, and redefines the scale of measurements, calculating the height as ten times the face, rather than eight times the head. The result is neither a portrait of a specific individual nor a faithful reproduction of a canon, but a theoretical reinterpretation of the human body, in which the subject is inscribed within a geometric grid that formalizes its proportions […].

This study marks the culmination of the first phase of research on proportions. After 1500, Leonardo’s interest shifts from the ideal to the particular, focusing on variations of the body in relation to age, sex, and movement. Leonardo recommends that artists study and measure their own bodies, exploring them with detachment as if they belonged to someone else, and comparing them with an ideal and universal body to become aware of the particularities of their own form.

The comparison with Dürer’s Self-Portrait […], almost twenty years later, highlights two different perspectives, both based on the same empirical methodology, where measurement is the main tool for understanding the body: Leonardo processes the collected data to arrive at a general principle that transcends individuality and synthesizes the human totality, while Dürer uses them to define his own corporeality at a specific moment, recording accidents and singularities.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Proportional Study of the Male Body (Vitruvian Man), 1490-1497, pen and ink on paper, with traces of metal stylus, silver or lead point, brown wash, compass work, 345 x 246 mm. Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia, inv. 228r © Archivio fotografico G.A.VE –courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura ‒ Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice

Tiziano Vecellio (1488/1490-1576), Betrothed Couple with Witness, ca. 1510, oil on canvas, 74.9 x 65.6 cm. Windsor, Royal Collection, inv. RCIN 403928 […]

The composition depicts two men and a woman: she leans her head on the shoulder of the man to her left, who embraces her and places his right hand on her breast. The lover’s gaze, directed towards the viewer, is calm and devoid of ostentatious sensuality. On the right, in the background, appears a second man, in a subordinate position relative to the centrality of the couple. Visible pentimenti allow us to identify in the painting the prototype of other known variants, including that of Casa Buonarroti (Shearman 1983, no. 65).

The attribution to Titian has long been questioned and debated with Paris Bordon and Giovanni Cariani (The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection 2007, no. 60). But the most enigmatic aspect remains the search for the subject, which scholars have variously identified: from Lucan’s Pharsalia (Book V, 1st century AD) ‒ already cited by Carlo Ridolfi (1648) ‒ to a novella by Matteo Bandello composed in those years (Cavalcaselle, Crowe 1871, II, p. 148). The gesture of the lover’s left hand helps clarify this: in the context of pre-Tridentine Venetian marriage rites, the gesture has a precise symbolic meaning as a sign of possession of the partner, while the man in the background appears as the “ring witness”, a witness to the marital union (Economopoulos 1992; The Courts of Marriage 2006, pp. 663-703). Several Venetian archive sources confirm these circumstances: for example, in 1512, a young groom, following a marriage contracted verba de presenti but not consummated, declares that he had «messo la man in sen et tochado le tette» in the presence of witnesses (Venice, Patriarchal Historical Archive, Curia 11, CM, vol. 12, Clara Marcello vs. Francesco de Orlandi). The role of the formal guarantor of the union is documented by sources as always close to the spouses during various phases of the rite, including the exchange of the ring, as well as the day after the first night of marriage.

The scene also recalls a popular visual type in genre images in Northern Europe, also reproduced in the engraving of the Coppia di amanti […]. In the case of Titian, not only the gesture but also the presence of a third person testify to the legitimacy of the rite.

Tiziano Vecellio (1488/1490-1576), Betrothed Couple with Witness, ca. 1510, oil on canvas, 74,9 x 65,6 cm. Windsor, Royal Collection, inv. RCIN 403928 © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

European manufacturing, Artificial arm, mid-16th century, iron and steel, 6 x 42 x 11 cm. Florence, Stibbert Museum, inv. 3819_A […]

In the 1500s, simple devices made of wood and leather, characteristic of prostheses since antiquity and appreciated for their ability to restore certain physiological functions, were gradually replaced ‒ at least among the upper classes of society ‒ by partially mechanized artificial limbs made of iron and steel, which for the first time in European history mimicked the natural appearance of lost joints. Mainly crafted by blacksmiths and armorers, these mechanical limbs were sophisticated engineering creations, custom-designed to integrate with the mutilated body with maximum functionality and ergonomics.

Upper prostheses, like the arm preserved at the Stibbert Museum, consisted of multiple articulated sections and featured fastening systems using rivets, screws, and a series of holes along the edges to secure padding. The snap button on the forearm allowed for unlocking and extending the limb into three different positions, while locking and release mechanisms ensured stability during movement. Steel, being more durable than iron, provided greater longevity and less oxidation.

Artificial hands replicated the anatomical structure with notable mechanical attention. The thumb was semi-closed and fixed, while the four fingers, also semi-closed, were articulated with a rotary mechanism adjustable to three grip positions. A button located on the wrist and internally connected to a toothed projection allowed for releasing the grip with a controlled movement. […] This balance between aesthetics and functionality facilitated the recovery of partial autonomy, allowing amputees to resume manual work ‒ who, unable to return to the battlefield, often found employment in arsenals ‒ and to maintain symbolic functions such as riding or wielding weapons. In any case, amputation was always a drastic decision, made when unavoidable by doctors and surgeons […].

Although the patient played a marginal role in the decision to amputate, psychological trauma and the desire to restore an identity conforming to social standards significantly influenced the post-amputation process. The adoption of a prosthesis mitigated the perception of deformity and also contributed to a more harmonious social and professional reintegration.

European manufacturing, Artificial arm, mid-16th century, iron and steel, 6 x 42 x 11 cm. Florence, Stibbert Museum, inv. 3819_A © Museo Stibbert

Translation of the texts curated by Carlotta Moro and published in the catalog of the exhibition Corpi moderni. The Making of the Body in Renaissance Venice. Leonardo, Michelangelo, Dürer, Giorgione, Marsilio Arte, Venice 2025.

INFO

Corpi moderni. The Making of the Body in Renaissance Venice. Leonardo, Michelangelo, Dürer, Giorgione

until 27 July 2025

GALLERIE DELL’ACCADEMIA

Campo della Carità ‒ Dorsoduro 1050, Venice

https://www.gallerieaccademia.it

Cover photo: Corpi moderni. La costruzione del corpo nella Venezia del Rinascimento. Leonardo, Michelangelo, Dürer, Giorgione, exhibition view, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice 2025. Photo Andrea Avezzù

Related Articles