Nicolas Berggruen, the philanthropist who is turning Palazzo Diedo into a cultural centre, has a pharaonic plan for the city of the Doges. It started in 2022 and his following words date back to that very year

“At a time when cultures are looking inward, and political barriers make it difficult for ideas to exchange freely, art can play a role in bringing the world together ‒ and Venice is the neutral nexus for it”.

Four hundred forty-five years ago ‒ or as Venetians view historical time, the week before last ‒ Patriarch Giovanni Trevisano laid the cornerstone for Andrea Palladio’s Church of the Most Holy Redeemer, Il Redentore, on the Giudecca.

The Republic’s Senate had commissioned the church to thank God for lifting the plague that had decimated Venice’s population for the previous two years ‒ a crisis that was a stunning reversal of fortune for the city, and in people’s eyes perhaps even a judgment from Heaven. The plague had descended almost immediately after Venice’s victory in the Battle of Lepanto, the world-shaking naval engagement that drove back the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean and gave Christian Europe a sudden, perhaps hubristic boost in confidence. The waning of the plague in 1577 therefore seemed a double recovery, not only from deadly illness but also from the onset of self-doubt that had followed the great military triumph. No wonder that when Il Redentore was at last consecrated in 1592, Venice erected a special pontoon bridge for the occasion, which the doge and senators crossed from the Zattere to attend the celebratory mass. It’s characteristic of Venetians, and striking evidence of the significance of this episode, that the same procession continues to be held today to commemorate the anniversary.

I can’t help thinking of this history today as visitors make their way to La Biennale de Venezia’s 59th International Art Exhibition while a devastating war is raging in Ukraine, two years after the plague of Covid locked down the city and the world. Here, too, is a ceremonial procession of sorts, as curators and art collectors, museum leaders and critics, artists and the fascinated enthusiasts who follow their work cross the water to Venice at the appointed time. These pilgrims travel to Venice because it hosts the world’s greatest art event: a combination of ritual and festival that must be attended, if only because people have done so for as long as anyone can remember. You might even call the observance of La Biennale an act of faith. It is undertaken in the conviction that art has the power to uplift, enlighten, and save, much as heaven’s power was said to have redeemed Venice from the plague.

Some people may ask, however, whether that faith is well placed. The plague of 1575-76 might have lifted because Heaven had extended its grace to a chastened city—or perhaps it happened because the Venetians had saved themselves, after a tragic delay, by instituting a quarantine. Similarly, the hundreds of artworks brought into Venice from around the world for La Biennale may move people to take positive action about the multitude of pressing subjects addressed, from climate change and the lingering impact of slavery and colonialism to the ravages of the current war and its attendant refugee crisis. Or perhaps, as some would allege, the audience at La Biennale already knows and accepts the opinions and attitudes expressed in these artworks and primarily derives a sense of self-justification, heightened status, and financial gain from viewing them.

In The Stones of Venice, John Ruskin argued that society and culture went into a long, slow decline in Venice as its citizens gradually stopped focusing their energy on religious ideals and looked instead to worldly wealth and pleasure. Are contemporary cultural critics too harsh when they ask what ideal is served by today’s pilgrimage to La Biennale?

I will answer as someone who believes that faith in the power of art is not at all misplaced, and as someone who is deeply committed not only to the history and traditions of Venice but to the city’s current vitality and potential for the future. Let me explain why I think the visual arts are more important than ever today, and why Venice is the place where they can and must flourish.

First, as John Ruskin knew, making art is a mode of thought and discovery. It can be a strongly compelling intellectual endeavor because of its appeal to the senses and emotions, and it has the capacity to be uniquely revealing because of its voracious approach to materials. Artists are exactly parallel to the so-called “primitive” subjects of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s studies, who found certain objects “good to think with.” The only difference is that artists today can find almost anything “good to think with.”

At the Berggruen Institute, we have encouraged and perhaps helped to advance, this omnivorous tendency through our Transformations of the Human School, in which we offer fellowships to artists who are interested in working with research scientists and engineers in artificial intelligence and biotechnology. In developing this program, we proposed that these new technologies pose challenges to our conventional notions of what it means to be human. We recognized that artists have already begun to explore the implications for how we see ourselves, behave toward others, and imagine our future. We believed the artists moving into these fields would benefit in their process from the experience of the latest research and development, and we wanted if possible to make art and philosophical investigation part of the research process for scientists and engineers. To inaugurate Transformations of the Human, we secured laboratory placements for the artists Nancy Baker Cahill, Ian Cheng, Stephanie Dinkins, Mara Eagle, Pierre Huyghe, Kahlil Joseph, Agnieszka Kurant, Rob Reynolds, Martine Syms, and Anicka Yi.

This is only one of the many examples of how contemporary artists are not only responding to the most important issues of our time—expressing opinions about them and urging action—but are conducting valuable research and contributing to knowledge and understanding. To visit the 59th International Art Exhibition at Venice is to plunge into the equivalent of a university-wide doctoral program, in which the dissertations are by turns startling, beautiful, and heartbreaking.

But the question remains: why Venice? La Biennale continues to exert an unequalled influence, thanks to its longevity and prestige, and also to the city’s great touristic allure. But many centuries have gone by since Venice was the center of the world’s trade routes and lines of cultural exchange. Despite its continuing artisanal strength, Venice is now a net importer, rather than producer and exporter, of artistic innovation. The title of “capital of world culture” passed on long ago to Paris, then New York, and today might more properly belong to Los Angeles or perhaps Shanghai.

Or so it might seem. I believe that Venice today, with a character that is at once deeply local and proudly transnational, can once again be a gateway between East and West. Rather than standing as a bulwark against half the world, as at the Battle of Lepanto, it can bring people together in peace. I also believe that Venice, apart from La Biennale, remains if not the Queen of the Adriatic then its cultural Sleeping Beauty. Its artists and civic leaders, social entrepreneurs and thinkers, are already at work and eager for their achievements to be recognized. The city is ready to stir again into artistic activity and creation, year-round.

The Fondazione di Venezia has been a leader in this revival, most recently by cooperating with the Berggruen Institute to convert the fabled Casa dei Tre Oci on the Giudecca into our European center of activity. Designed by the artist Mario De Maria as his home and studio, the century-old neo-Gothic house has a long history of hosting artists and intellectuals, including participants in La Biennale, and serving as a venue for cultural meetings and debates. Beginning in 2012, under the auspices of the Fondazione di Venezia, the Casa dei Tre Oci has been a public showplace for important photography exhibitions. These exhibitions will continue—and now, as a headquarters of the Berggruen Institute, it will host an international program of summits, workshops, symposia, and exhibitions in the visual arts and architecture.

Casa dei Tre Oci represents our commitment for restoring Venice as a primary global gateway for ideas and this is now extended to Palazzo Diedo, a site which will nurture artistic creation. This palazzo in the heart of Canareggio was designed by Andrea Tirali for one of Venice’s oldest families, the Diedo, and had been a property of the City of Venice since 1888. Now it is the home of the new Berggruen Arts & Culture, an initiative which will host exhibitions as well as installations, symposia, and an artist-in-residence program with the aim of fostering the creation of art in Venice.

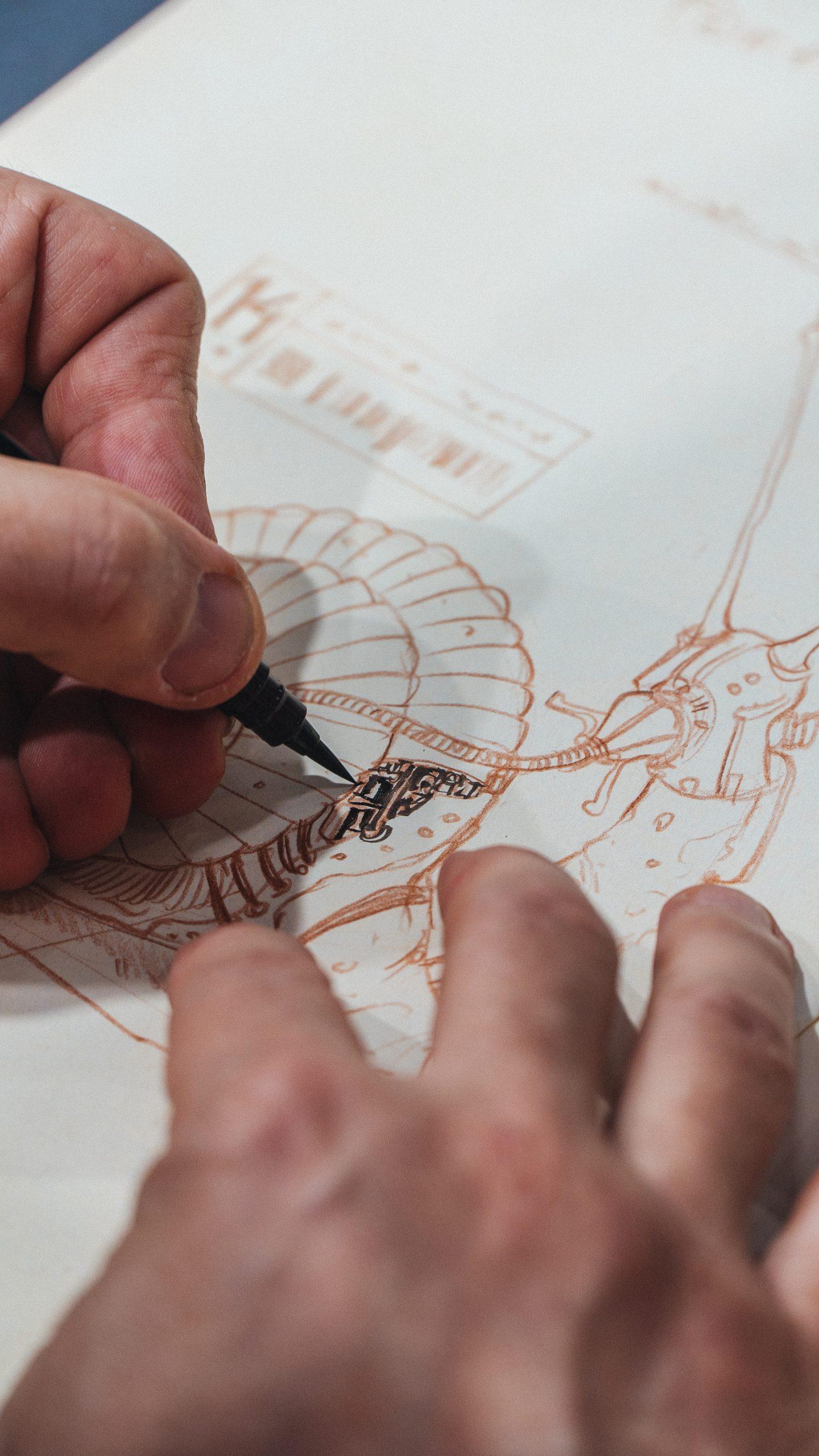

Palazzo Diedo is currently undergoing a renovation and restoration; we have appointed Venice-born international curator Mario Codognato as artistic director; and have welcomed Sterling Ruby as its first artist-in-residence. Known for his philosophical investigations into a dazzling range of techniques and media, both traditional and new, Ruby is using the Palazzo Diedo to reflect upon, and bring into the present, the heritage of artmaking and craft in Venice. Although it is estimated that the Palazzo Diedo will not open to the public with its full program until 2024, Ruby is currently at work on the first phase of a long-term installation project, HEX, the first element of which will be on view throughout the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale.

For those of us ‒ and there are many ‒ who long to see Venice resume its leading role as a generator of artistic innovation and as a meeting place, and instigator, of new ideas, the project of assisting in this revival does in fact require a leap of faith. But let us be clear: this is not the faith that, according to cliché, unthinkingly substitutes artworks for religion. The advocates for Venice do not worship contemporary art as an idol but respect it as a vital, indispensable component of the world’s intellectual life ‒ and we see Venice as the city that is historically, geographically, and culturally poised to advance today’s most consequential works of art into the global conversation.

To invest oneself in this belief is to have faith that the sufferings caused by pandemics and war have not put an end to our creative capacities but may instead inspire us to use them more wisely and vigorously. We, too, may work to restore ideas and art to Venice as our answer to pestilence and violence ‒ if not a church, then a structure of continuing encouragement and support for thinkers and artists in all disciplines. If the past teaches us anything, it’s that the work of our own hands might also be able to stand for four hundred years.

By Nicolas Berggruen

BIO

Nicolas Berggruen (Paris, 1961) is founder and president of the Berggruen Institute and has spearheaded its growth, affirming its presence in Los Angeles, Beijing and Venice. Focusing on the major transformations of the human condition determined by such factors as climate change, the reorganisation of the international economy and politics, and advancements in science and technology, the Institute seeks to connect and develop ideas in the humanities with the aim of achieving practical improvements in governance across cultures, disciplines and political boundaries.

Photo cover: Nicolas Berggruen and Mario Codognato at Palazzo Diedo, Venice 2022. Photo Luca Zanon

Related Articles