The Palazzo Ducale in Genoa pays tribute to Paolo Di Paolo on the centenary of his birth with an exhibition curated by Giovanna Calvenzi and Silvia Di Paolo. Three hundred photographs, many of which are unpublished and, for the first time, also in colour, together with archive material, vintage magazines, videos and original documents, retrace the author’s career from its beginnings in 1953. To learn more about his story, we suggest reading the text by curator Giovanna Calvenzi published in the catalogue edited by Marsilio Arte

What does Greta Garbo have to do with it?

“With an attentive, insightful and sensitive gaze, Paolo Di Paolo has been able to document the changes in the urban and rural landscape, as well as the emergence of new lifestyles, with rare empathy capturing the complex coexistence between the memory of a world in dissolution and the dawn of a new era. This is why we number him among the most important Italian photographers of the second half of the twentieth century.” With these words, Antonella Polimeni, rector of the Sapienza Università di Roma, recalled the presentation of the Honorary Master’s Degree to Paolo Di Paolo, one day before his ninety-eighth birthday, on May 16, 2023. The crowning achievement of the intense life and extraordinary professional career, unusual in its strangeness, of Paolo Di Paolo, whom I met for the first time in 2018. Quite unexpectedly I had received a phone call from Bartolomeo Pietromarchi, then director of MAXXI Arte in Rome, who asked me whether I would care to curate an exhibition by Paolo Di Paolo. With some embarrassment I replied that I did not know him (in retrospect I have to add that Paolo Di Paolo would remind me of this “ignorance” on many occasions). Very elegantly, without batting an eyelid, Pietromarchi sent me a selection of photographs. I was immediately excited. On the monitor I saw images of a kind that I had never seen before, which recounted life on the Italian beaches, life in Rome and Japan, as well as empathic, masterful portraits of the most famous actors of the fifties and sixties. I confess that I was speechless. This was the start, with my inevitable sense of guilt and oft-remembered shame at my ignorance, of a professional relationship and friendship that would develop into a close tie with Paolo Di Paolo, with his work, his daughter Silvia, his wife Elena, and today also his hometown, Larino, in Molise.

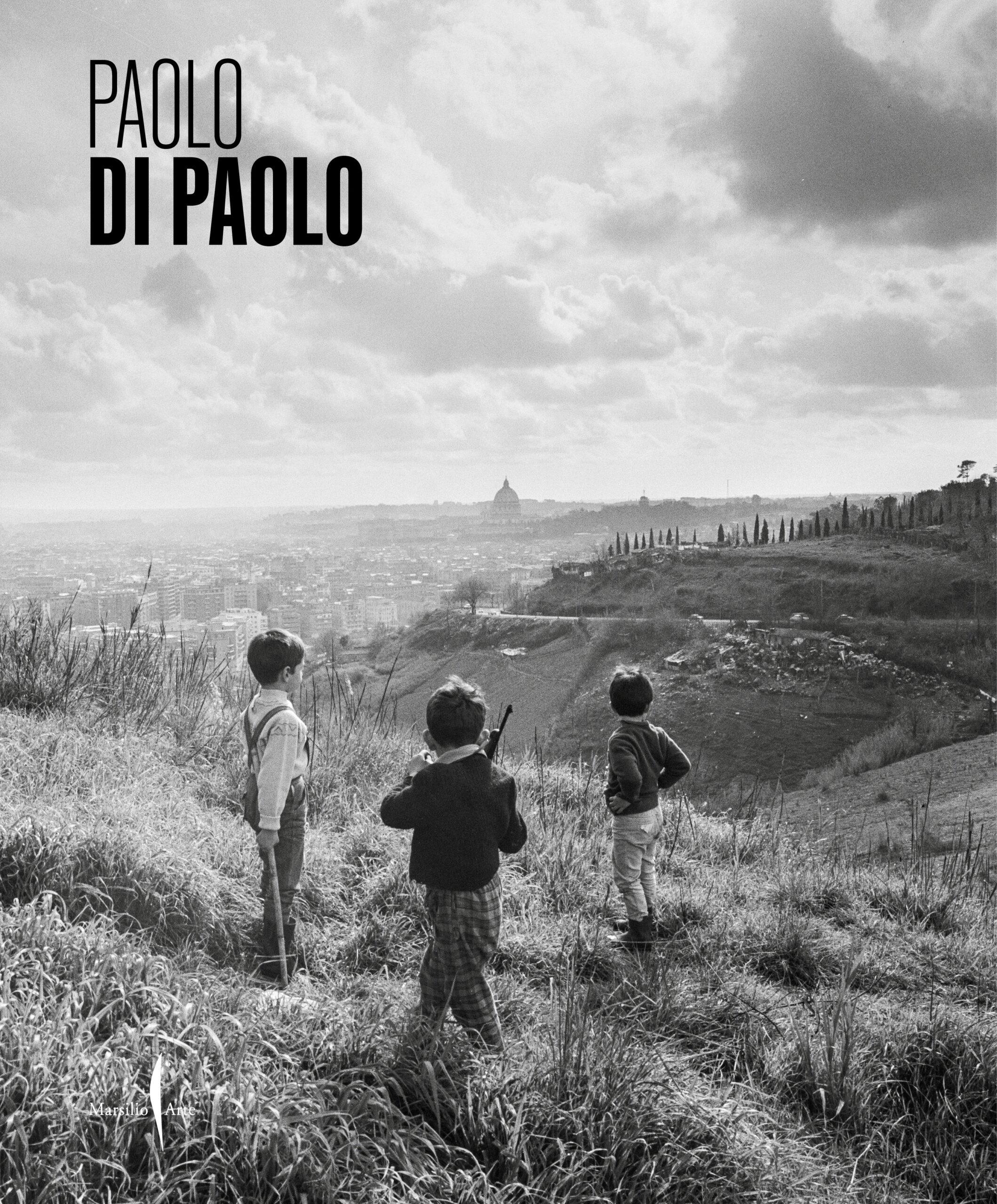

The exhibition at the MAXXI in Rome, entitled Paolo Di Paolo. Mondo perduto, was therefore inaugurated on April 16, 2019, after a few months’ work with Paolo and Silvia to decide together how to present not only a sequence of photographs but a whole world that had remained buried in the cellar of their home for almost fifty years. Paolo had an excellent memory for facts and names but dates mattered very little to him. He also had, as happens to the best authors, a particular affection for some images that I considered lacking in significance, and with mutual grace we tried to direct our different opinions towards a satisfactory common result. In the production of the book that accompanied the exhibition, it had been easy to come to an agreement. But Paolo had taken back the rights granted to me for the book, and I met with several surprises. Images that we had discarded were exhibited with large captions, the portraits of Oriana Fallaci or Raquel Welch had become refined and amusing sequences, and even the gigantic image that opened the exhibition (and which is now on the cover of this book) had been found by Silvia Di Paolo only after the book was completed. (The photo had appeared in Il Mondo unsigned, so that Paolo Di Paolo was unsure that he had actually taken it.)

Translating the complexity of a professional life and choices that were difficult to understand, then, did not prove easy. I felt the need not only to reconstruct his personal story but also to lay the groundwork to place the figure of Paolo Di Paolo in the historical period that Italy, publishing and photography were passing through when the young man from Molise who had recently arrived in Rome decided that photography could become his profession. And I wrote: “In 1954, when Paolo Di Paolo started working as a photographer, believing in it, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, Edouard Boubat and Izis, Brassaï were working in Paris and around the world, Bill Brandt was living and working in London, Robert Frank was leaving for the United States, where André Kertész had already been settled for over a decade. Robert Capa would die in Thái Binh, Vietnam, in May, and Edward Weston had already stopped working, while Richard Avedon and Irving Penn in New York were on the rise. But the list continues: William Klein would soon publish his first book, Life is Good & Good for You in New York, Helmut Newton was not yet Helmut Newton and worked only for Vogue Australia. In Italy, Federico Patellani was the most accurate observer of contemporary reality, Alberto Lattuada had long since abandoned photography for the cinema, and Gianni Berengo Gardin was still an amateur photographer in Venice. The Magnum agency was already seven years old and in 1955 the young Tazio Secchiaroli founded the Roma Press Photo agency, specializing in political news and social gossip.” This brief reflection on the internationally best known authors and what they were creating in 1954 was a strategy to place the young Paolo Di Paolo on the photographic scene. A scene that, however, the times and systems of dissemination of information in those years certainly did not enable him to know, largely because his overriding interest was in philosophy. So Paolo Di Paolo arrived in Rome, and thanks to his interests and acquaintances, he entered the heart of the reality of Rome, and photography practically invested him immediately. He was the victim of love at first sight for a small, magnificent Leica, and his love for the object soon grew into a love for photography. He contributed to a poetry and photography magazine, Montaggio, and worked on its graphic design, then immediately afterwards began to contribute to Il Mondo, a periodical directed by Mario Pannunzio.

Il Mondo was a magazine that today we might describe as elitist, with more contributors than readers, as Pannunzio himself said. It had existed for just over five years and had quickly become an essential point of arrival for photographers, including some from outside Italy. During the seventeen years of its existence, it published 890 issues, the last on March 8, 1966, with a practically identical structure: sixteen pages, always with the same graphic design, from ten to twenty Italian or foreign photographs in each issue, selected to be independent, not illustrations of the texts. For Paolo Di Paolo, Il Mondo became his most important contact, though in the meantime he had begun to contribute to Tempo and La Settimana Incom Illustrata, in practice the most important periodicals of the day. Di Paolo was Pannunzio’s favorite photographer, the most published (573 photographs), the first whose images were signed, and also the author of a heartfelt telegram sent to the editor when the journal closed: “For me and for other friends, the ambition to be photographers dies today.”3 With great pleasure, Paolo Di Paolo loved to recall his collaboration with Il Mondo, his visits to the editorial office, the ritual of presenting the photos to the director, his working method and the way he chose the images.

So much so that, on the occasion of his exhibition at the MAXXI, he decided to reconstruct Pannunzio’s studio with scholarly accuracy by searching the antiques markets for the same furnishings, the same accessories.

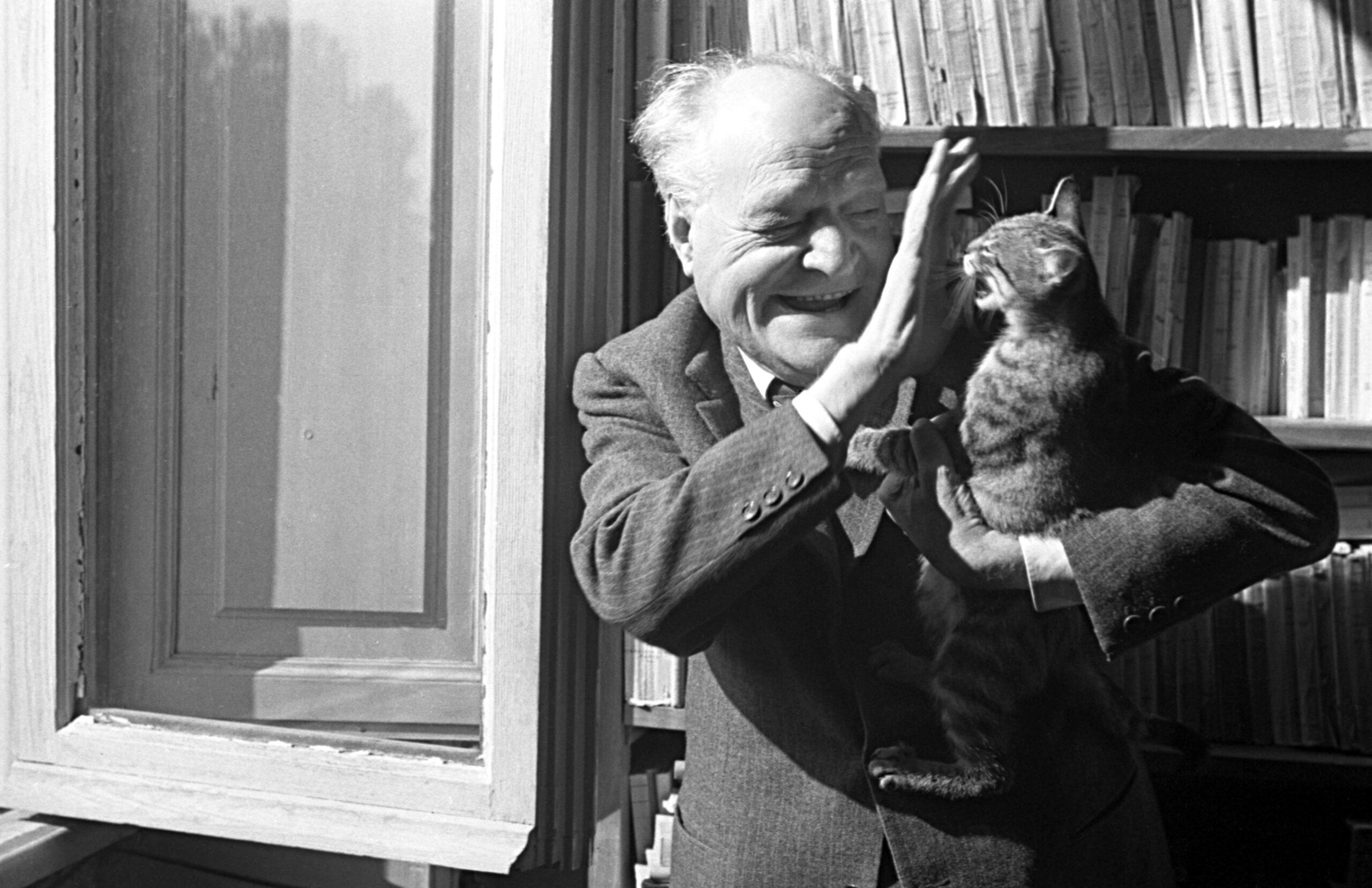

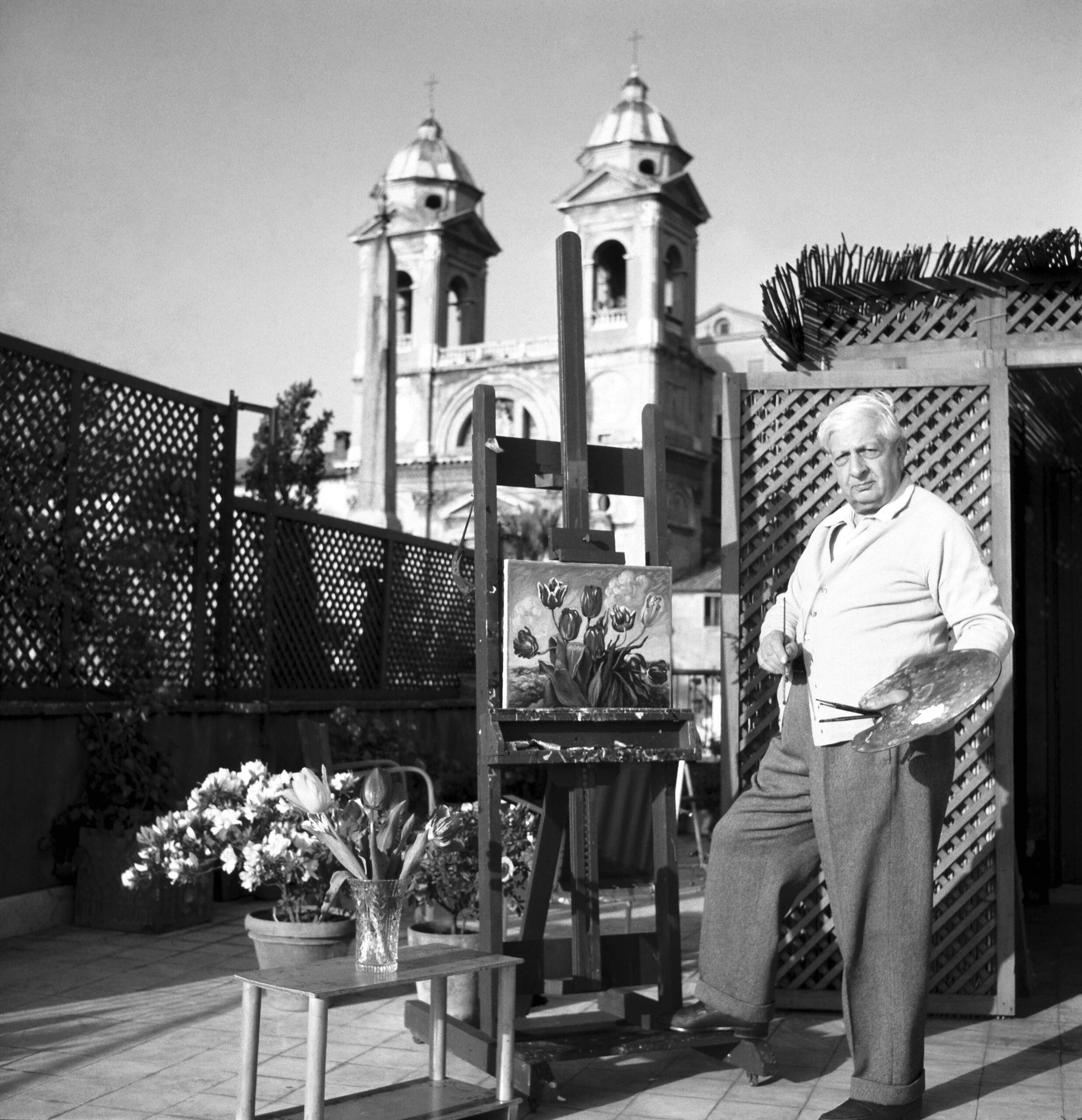

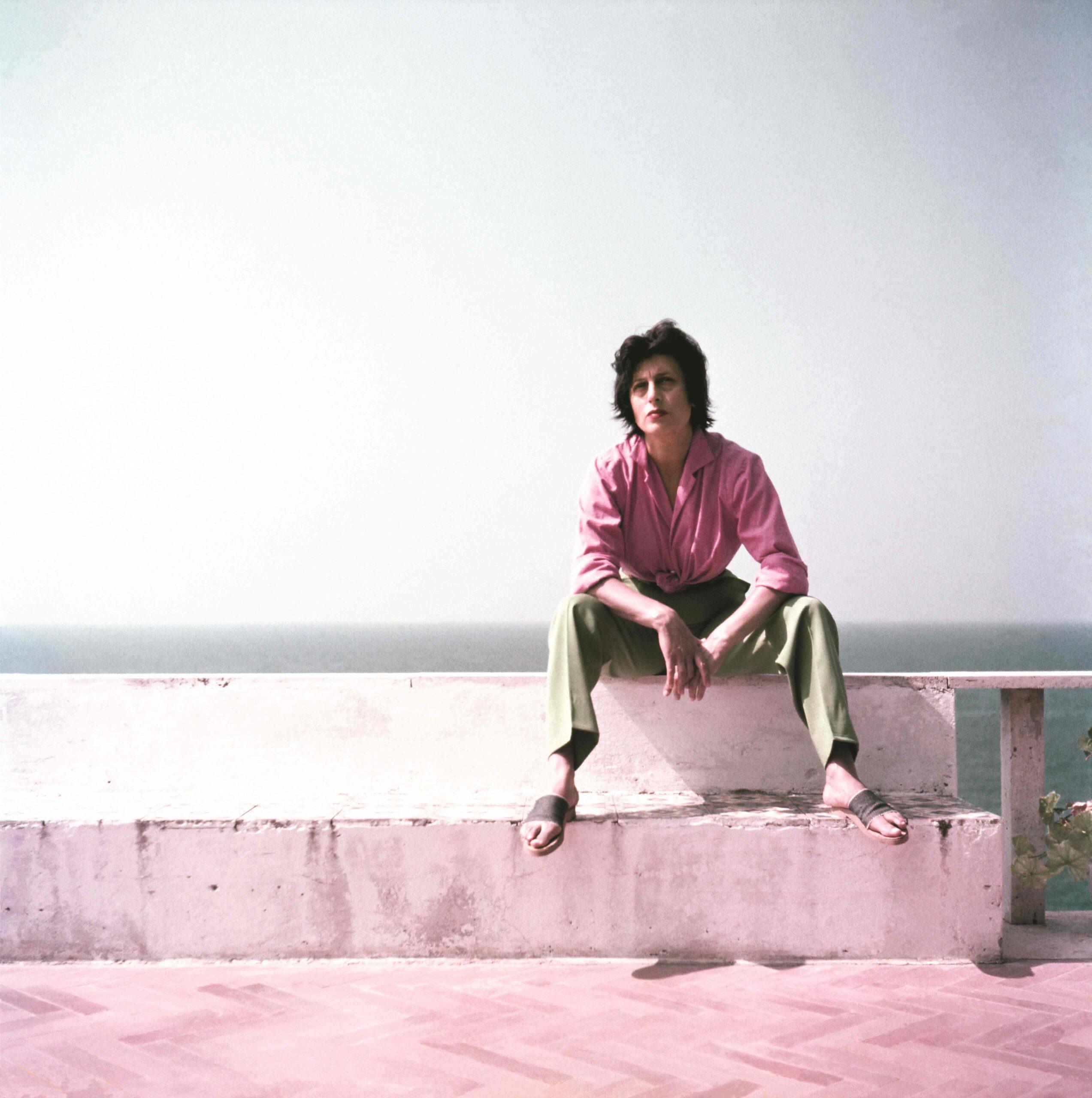

Italian publishing in the fifties was experiencing a period of particular fervor. Illustrated magazines had high print runs and excellent circulations. Reconstruction had begun, after the war and twenty years of fascism, and the economic boom was upon us. However, an ISTAT census in 1951 presented Italy as a predominantly agricultural country with 47 million inhabitants, an illiteracy rate of 12.9% and a semi-illiteracy rate of 46.3%. So photography was an excellent source of information for the part of the population that could see better than it could read. The cinema had returned to Rome and the presence of actresses, actors and filmmakers in the city had to be documented. At the suggestion of a friend, Paolo Di Paolo photographed a couple of famous newly-engaged couples, Lucia Bosé, Miss Italy 1947, and the bullfighter Luis Dominguín, who posed for him joking and bantering. This would always be the register that would characterize his relationship with the art world: respect, cheerful irony, empathy with his subjects, but also an outstanding ability to recount people and whatever surrounded them, putting them at the center of images that still retain their narrative strength unaltered today. It was an extraordinarily successful beginning, and it opened the doors of the finest weekly magazines to him. By the end of the fifties Paolo Di Paolo can be said to have become an established photographer. He declared: “I felt free. I was doing a wonderful job, I knew a lot of people. Every morning I woke up and could decide what I was going to do.” In 1959 he was the most highly appreciated contributor to Tempo, directed by Arturo Tofanelli, and for another magazine published by Aldo Palazzi Editore, Successo (a monthly periodical also directed by Tofanelli), he created an epic journey devoted to the Italians’ vacations. La lunga strada di sabbia is a story in images with texts by Pier Paolo Pasolini that became an essential achievement in the history of Italian photography. Pasolini and Di Paolo set off together from Rome, their first stop, towards the French border. They were an unusual pair of traveling companions, not very compatible at first. Paolo Di Paolo would later recall: “He was searching for a lost world, of literary ghosts, an Italy that no longer existed, I was searching for an Italy that looked to the future.”

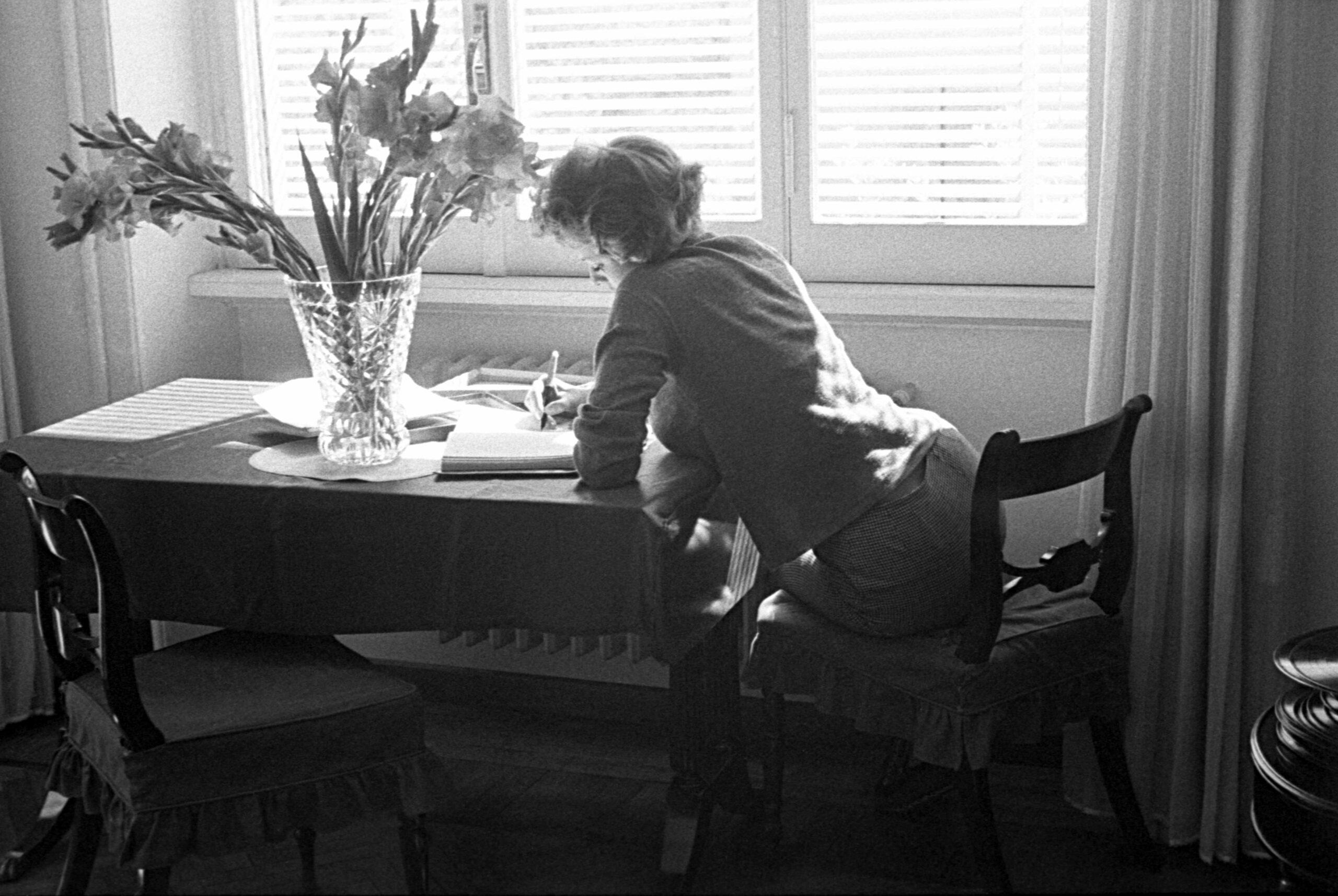

And yet their journey (which they performed separately after the first stage) was a great success. Palazzi’s monthly would publish about twenty images in three episodes, not necessarily the most interesting. In 2023, thanks to lengthy work in the archives, Silvia Di Paolo was able to give us a volume with 160 images4 that tell us not only about “the Italians’s vacations” in 1959 but about a world that would soon disappear.

In the following decade Paolo Di Paolo continued with unstoppable success to photograph leading figures in the worlds of culture, art and cinema, and travel the world, producing stories that ranged from the port of Genoa to Iran, Austria, Japan, New York, Texas, Milan and Moscow. He began working with Irene Brin. He recalled: “She was the most snobbish of Italian journalists, the daughter of a Ligurian general and an Italian- Austrian aristocrat. In 1934 she had begun to write for Il Lavoro in Genoa where Leo Longanesi discovered her. “Your name will be Irene Brin,” he told her, inviting her to contribute to Omnibus, and Maria Vittoria Rossi disappeared forever. She moved to Rome, married Gaspero Del Corso and after the war they opened the very refined Galleria l’Obelisco di Gaspero e Maria Del Corso in Via Sistina.”

But things were changing. In 1966 Il Mondo folded. In 1968 the editorship of Tempo passed from Arturo Tofanelli to Nicola Cattedra, and the new front of photo shoots for fashion magazines was not as satisfactory as he would have liked. Publishing and photography were being transformed, the times were changing. Political commitment in 1968 and the period after 1968 was accompanied by the work of the paparazzi and a decline in interest in illustrated periodicals in part due to the growth of TV ratings. Paolo Di Paolo, who throughout his professional life had declared that he “photographed for pleasure,” was not sure that the future that lay ahead would bring him the same sense of fulfilment. He was 43 years old; he married Elena, left Rome and went to live in the countryside. His photographic archive, his life as a photographer, ended up in the cellar.

Where, almost fifty years later, fortunately for her and us, his daughter Silvia would rediscover that “lost world,” which we have not yet finished exploring. On the day of the inauguration of his major exhibition at the MAXXI in 2018, Paolo Di Paolo presented himself to the public with a cheerful, magnificent, definition of himself: “I am the Greta Garbo of photography.”

Giovanna Calvenzi

Text taken from the catalogue of the exhibition PAOLO DI PAOLO. Fotografie ritrovate, Marsilio Arte, Venice 2025

BIO

From 1985 to 2019, Giovanna Calvenzi was photo editor for several Italian magazines. In 1998, she was artistic director of the Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie in Arles, in 2002 guest curator of Photo España in Madrid, and in 2014 artistic delegate of the Mois de la Photo in Paris. She has taught history of photography and photo editing in Milan and Bologna and is actively involved in the study of contemporary photography. Since 2013, she has been in charge of the Gabriele Basilico Archive and from 2016 to 2022 she was president of the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Cinisello Balsamo-Milan.

INFO

PAOLO DI PAOLO. Fotografie ritrovate

until 6 April 2026

PALAZZO DUCALE – Sottoporticato

Piazza Matteotti 9, Genoa

https://palazzoducale.genova.it/

Related products

Related Articles