“For a long time I was Maurizio Cattelan”. This is how internationally renowned curator Massimiliano Gioni starts his reflections on his relationship with Maurizio Cattelan following the publication of the book “Beware of Yourself”, edited by Marsilio Arte and Pirelli HangarBicocca, which covers almost forty years of the artist’s career. Here’s how this story of friendship, work and complicity continues

For a long time I was Maurizio Cattelan. I met Maurizio in late 1997, and I seem to recall that the day after that very first meeting, I was already doing an interview in his stead on the Italian national radio. From then until 2006, with a few instances in the years that followed, I wrote all his texts and press releases, did hundreds of interviews on his behalf, made dozens of television appearances, and gave lectures in his place at theatres and universities around the world—France, Germany, and Japan, by way of Venice, San Francisco, and New York. I was Cattelan at Yale, the New School, and New York University, where a student, shocked by my performance as an impostor, wrote a fiery letter to the dean demanding a refund of her tuition fees and the dismissal of the professor. I wrote his keynote address for the honorary degree in Sociology he received at the University of Trento and spoke in his stead about blasphemy and sainthood on Vatican Radio. During the media storm sparked by his hanged children in Milan, I spoke on television, first as myself and then as him.

I was his voice and all the while fabricated lies and half-truths. “There are no facts, only interpretations” was one of my catchphrases when I was Cattelan: I had stolen it from Nietzsche. “Truth is a function of effectiveness”, on the other hand, if I’m not mistaken, I’d taken from Algirdas Greimas. In the late 1990s, post-truth wasn’t yet a topic of discussion, but it was already clear to Maurizio that in a communication society, narratives mattered more than facts. At the time, Cattelan was still shy and awkward, incapable or perhaps uninterested in speaking about his work in public: “Writing is not my job,” read one of his first works published by his imaginary publishing house, “Edizioni dell’Obbligo [Compulsory Publishing Inc.].” That was perhaps why he entrusted me, without any kind of ceremony or official mandate, with the public interpretation of his work, thus setting in motion an infinite series of meanings and possible readings, all equally legitimate. There was no secret pact or pre-planned strategy. I had carte blanche and could say whatever I wanted, although—after each interview—Maurizio had a few suggestions. Though taciturn, Cattelan is an excellent editor: all his work is a cut-and-paste, animated by the drive to achieve a perfect synthesis of clarity and complexity.

For my part, I combined a bit of everything in my answers: from Lenny Bruce to Philip Roth, Carmelo Bene and Umberto Eco, the Simpsons, South Park, and a bit of Derrida. I quoted, misquoted, and made things up, alternating sincerity and mischief. The interviews were meant to seem plausible but at the same time slightly off, estranged: Bertolt Brecht meets Umberto Simonetta, at a bar. What I liked about this strange relationship was that it destroyed any sense of supposed critical distance and objectivity that, in theory, a critic should maintain in relation to artworks and artists. And I imagined myself as the new evolution of a militant critic: no longer signing manifestos but actually lending my words to artists.

Maurizio paid me: if I’m not mistaken, $500 a month, which, along with the thousand Flash Art gave me, was enough to survive in New York, as long as I didn’t have to pay rent. So I lived like a sort of au pair, hosted by art critic Roselee Goldberg. During that period—and for many years later—Maurizio and I saw or spoke to each other every day. Along with our friend Ali Subotnick—with whom we have founded the Wrong Gallery, created a couple of magazines, and curated exhibitions around the world—Maurizio had effectively become my adoptive and stray family. When I didn’t have a place in New York, I slept on a mattress thrown on the floor in the living room of the apartment Maurizio shared with a friend. For a few years, during the preparations for the 2006 Berlin Biennale, we even lived together like two students abroad. Back then, Maurizio would wake up very early to go swimming and eat cucumbers for breakfast, sometimes watching a TV series at seven in the morning. As Henri Pierre Roché said of his friend Marcel Duchamp: his greatest masterpiece was how he used time.

For years, Maurizio was my friend, mentor, confidant, older brother, reckless uncle, exploitative boss, generous accomplice, travelling companion, alter ego, and practically ex-husband. We were even almost arrested for tearing out pages from books to produce his magazine Permanent Food; we’re both banned from the Barnes & Nobles bookstore chain.

It was therefore with some apprehension that I learned of the imminent release of this new unreasonable catalogue raisonné, which collects all of “his” writings. The book is packed with images, stories, and insights. But who says “I” in this book? The notes at the end of the volume list various impostors and charlatans like me. When, around 2006, I decided to exit the scene, because I was starting to be known as myself, Cattelan quickly recruited other ghostwriters and alter egos. And, truth be told, even when I was in the most unbridled phase of my Cattelanism, every once in a while I would read interviews of his that didn’t seem like they’d been written by me. How many people were there speaking in Cattelan’s tongues?

“You don’t know who I think I am,” said Vincenzo Sparagna, founder of Frigidaire, a magazine Maurizio read when he was young. The idea that the self contains multitudes—or, indeed, that there isn’t even a self at all, but only endless versions of us—was a problem already clear to Walt Whitman, Erving Goffman, Judith Butler, and even the Italian 1970s boy band The Pooh, which sang of “infinite we”, an expression Maurizio would have liked. Cattelan goes through art and life staging a continuous performance of the self, wearing a series of masks that hide no subject—naked masks, Fausto Pirandello called them. In an age when we are nothing but images reflected in the eyes or cell phones of others, who has the right to say “I”?

As beautiful as this book is, it also makes me a little sad because, on the one hand, that explosion of the self should be joyful—if I can become someone else, the possibilities for growth and reinvention should be endless—but, on the other, there’s also a sense of melancholy and loss in watching the self fray into so many shreds. And then, despite all the possible adventures I could embark on, and have embarked on, in the end I always remain the same old me, ultimately identical to everybody else. On the last page of this new book, Cattelan—or someone else for him—thanks “himself”: but why does even the most manifold being want to say “I”?

Massimiliano Gioni

Realized in collaboration with Il Sole 24 Ore Sunday edition

BIO

Massimiliano Gioni is the Artistic Director of the New Museum in New York, where he has presented numerous exhibitions by international artists, including Judy Chicago, Theaster Gates, Carsten Hōller, Ragnar Kjartansson, Faith Ringgold, Pipilotti Rist, and Anri Sala.

In the past, he has curated major international exhibitions, including the 55th Venice Biennale (2013), the Gwangjiu Biennale (2010), the first Triennial of the New Museum (with Lauren Cornell and Laura Hoptman), the 4th Berlin Biennale (with Maurizio Cattelan and Ali Subotnick) and Manifesta 5 (with Marta Kuzma).

In Milan, Gioni has been directing the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi since 2002, for which he has curated public art projects and themed exhibitions, rediscovering forgotten and symbolic places in the city of Milan.

His latest exhibition in Milan with the Fondazione Trussardi – Fata Morgana: Memories of the Invisible – is on view at Palazzo Morando until 4 January 2026.

Captions:

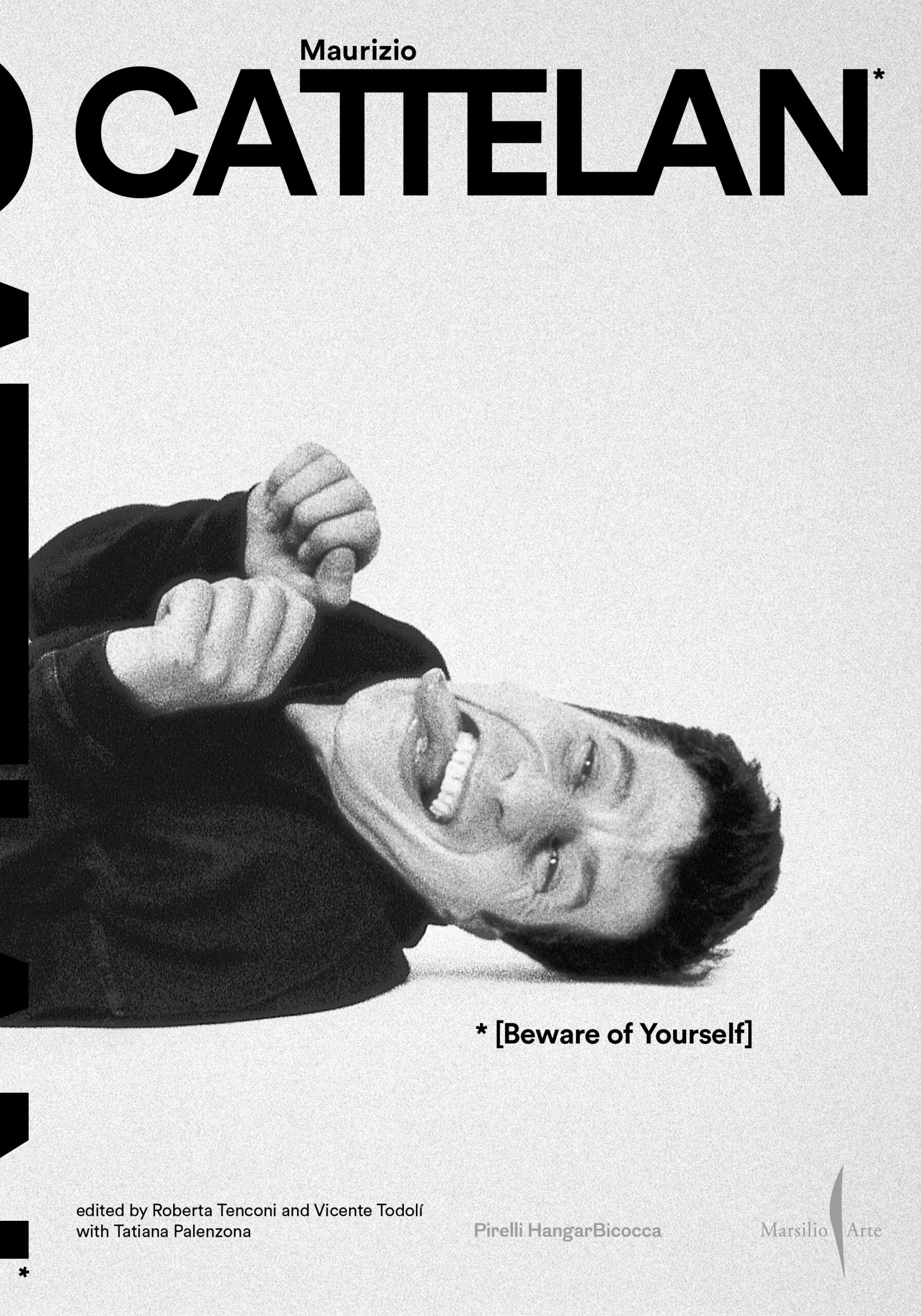

The cover of Beware of Yourself. Pirelli HangarBicocca and Marsilio Arte, 2025

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2000. Not Afraid of Love, Monnaie de Paris, Paris, 2016

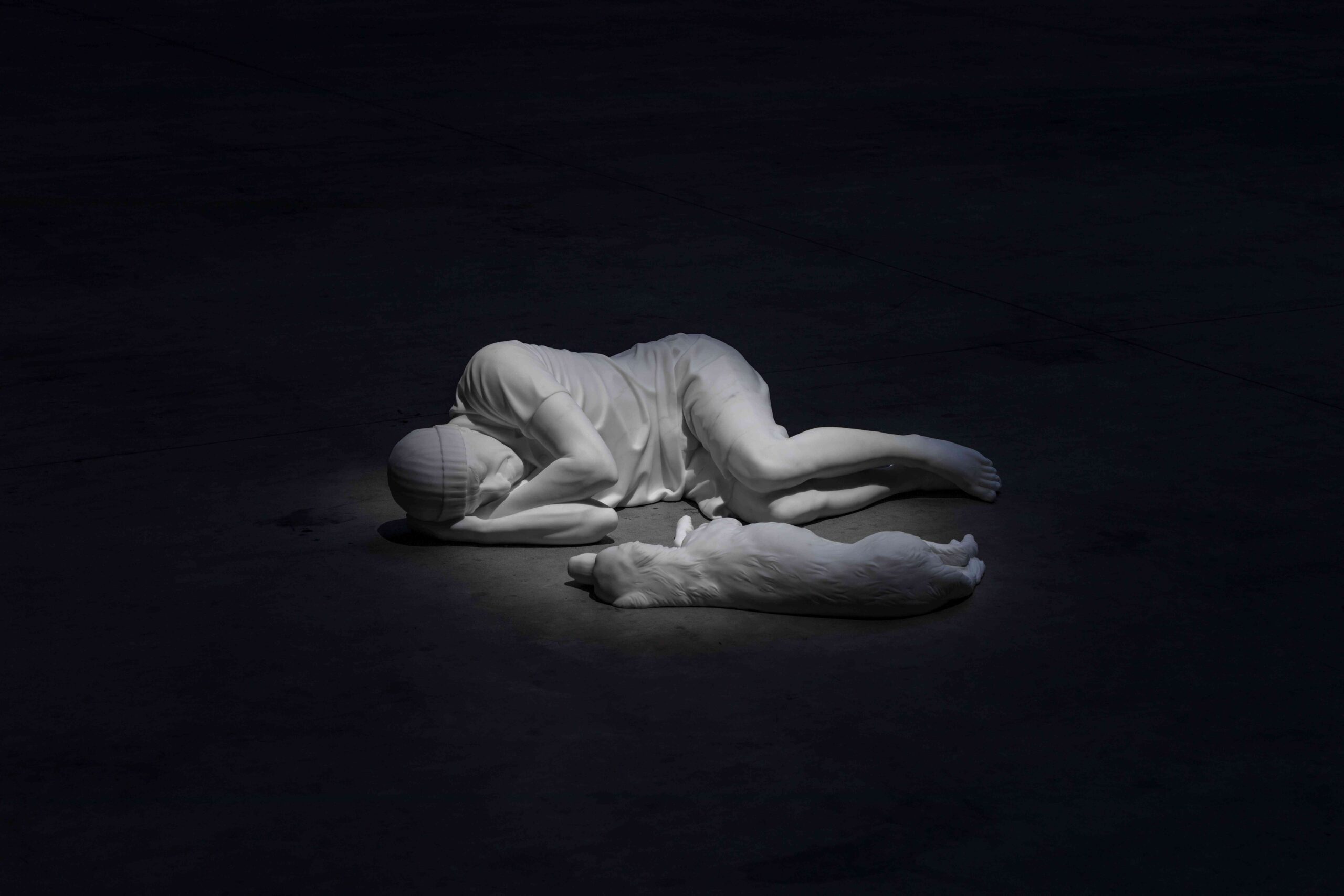

Maurizio Cattelan, Breath, 2021. Maurizio Cattelan. Breath Ghosts Blind, curated by Roberta Tenconi and Vicente Todolí, Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 15 July 2021 – 20 February 2022 (solo exhibition). Photo Zeno Zotti

Maurizio Cattelan, One, 2025. Maurizio Cattelan. Seasons, GAMeC – Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo and other venues, 2025, installation at the Rotonda dei Mille, Bergamo. Photo Lorenzo Palmieri

Maurizio Cattelan, Father, 2021. With my Eyes, curated by Chiara Parisi and

Bruno Racine, 60th Venice Biennale, 20 April – 24 November 2024 (group show), The Holy See Pavilion, installation at Venice-Giudecca Women’s Prison. Photo Zeno Zotti

Maurizio Cattelan, Love Saves Life, 1995. Skulptur. Projekte in Münster 1997, curated by Kasper König, Münster, 22 June – 28 September 1997 (group show), installation at the Westfälisches Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte. Photo Roman Mensing

Maurizio Cattelan, Maurizio Cattelan. All, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2011 – 2012. Photo Zeno Zotti

Maurizio Cattelan portrayed by Pierpaolo Ferrari, July 2019. Photo Pierpaolo Ferrari

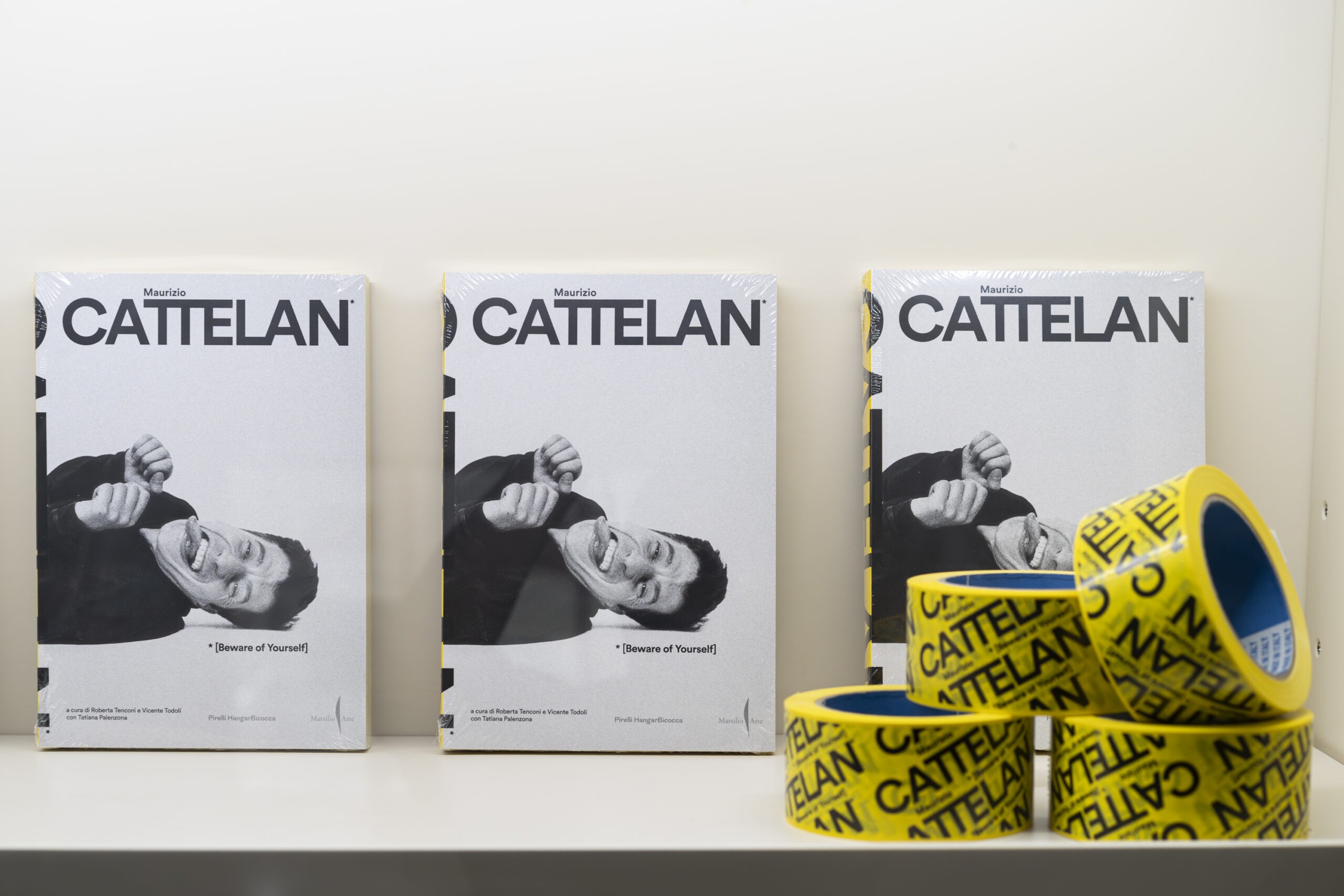

The book signing of Beware of Yourself, Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2025. Photo Lorenzo Palmieri (cover photo)

Related products

Related Articles