Created by Phaidon and published in Italy by Marsilio Arte, “The Christmas Book” contains within its pages a journey through art, design and pop culture, revealing a series of unexpected connections. We asked journalist Antonio Mancinelli to leaf through it with us

It’s the holiday that none of us asked for, but which we all inevitably end up taking part in. You can be an atheist, an agnostic, a devotee only of the latest season of Netflix, but when mid-December rolls around, all protestations are useless: we enter, without realizing it, into the enchanted and slightly bizarre territory of the holidays.

Even the most disillusioned intellectual, who normally only reads Camus and listens to atonal jazz, finds themselves sighing in front of a decorated fir tree, as if it could recreate the naivety of a childhood that probably never existed.

Even our idea of tradition in general is a paradox of delicious, exquisite hypocrisy: the family toast is done more for the use and consumption of social media than any convivial spirit. We become possessed by the unshakeable conviction that, in the end, the important thing is to “be together” as if we hadn’t seen each other all year, as if a lunch were not just the pretext for yet another illusion of harmony.

A shiny, tasty trap, a “shining deception”, Plato would have said. But boy, do we love it. All of us. Passionately.

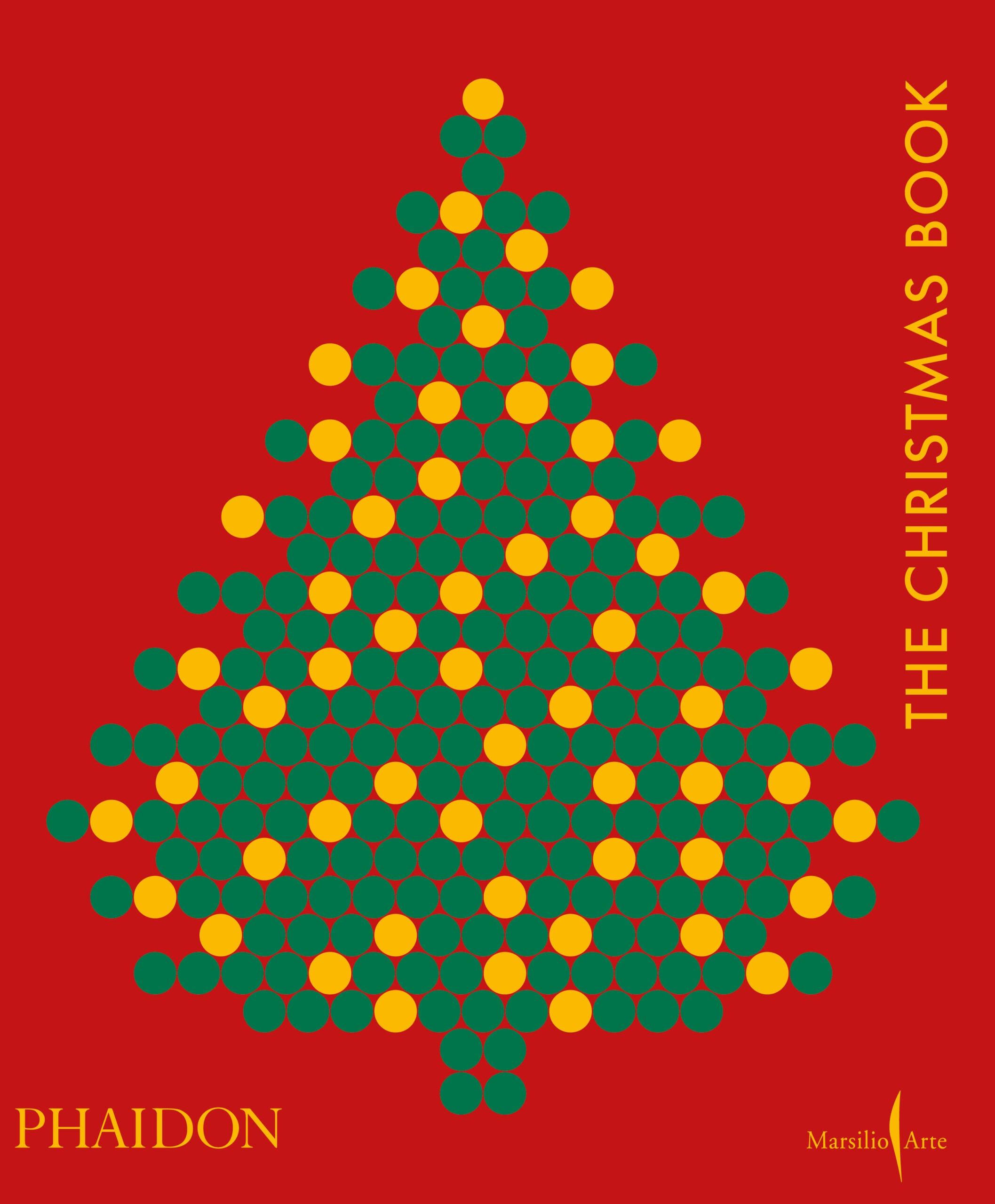

Collating and collecting (almost) everything that under the extended concept of “Christmas” has inspired art, food, fashion, culture, comics over nearly a millennium, is The Christmas Book, published in Italy by Marsilio Arte. A sumptuous, illustrated and whimsically eclectic work, the celebration of a cultural phenomenon that has transcended the boundaries of religion to become a secular celebration, a collective performance of desires, regrets and appetites.

With a subtle humour and an almost anthropological precision, the volume delights in cataloguing everything that 25 December represents in the West and beyond, composing a visual mosaic of over 200 images that range from sacred art to Pop Art, from medieval decorations to 1950s advertisements, passing through works by illustrious artists such as Botticelli, Andy Warhol, Norman Rockwell, Grandma Moses, and even the drawings of The Snowman by Raymond Briggs. It is a true visual anthology of illusions and liturgies, a catalogue of symbols that reminds us that Christmas is, for much of the world, one of the few occasions on which popular culture manages to don a splendid and pseudo-divine guise.

Take, for example, Shirazeh Houshiary’s upside-down Christmas tree hanging from the ceiling of the Tate Britain like a modernist allegory, or J.R.R. Tolkien’s handwritten Santa Claus letters to his children, small masterpieces of calligraphy and fantasy that sit alongside Mariah Carey’s ubiquitous and slightly irritating Merry Christmas album in this volume. The contrast is delightful, almost satirical: here contemporary art gives a nod to memory alongside the sentimental nostalgia of a widely shared feeling.

The essays by Sam Bilton, Dolph Gotelli and David Trigg explore traditional holiday foods and drinks, Santa Claus throughout history and the pious origins of the holiday, in a visual journey guided by a tender and mischievous wisdom that mixes the sacred and the profane, the high and the low: as if to suggest that Christmas is, after all, an enormous hall of mirrors in which everyone sees the image of what they desire.

I loved the beautiful dissertation dedicated to food ‒ edited by Sam Bilton, an expert in gastronomic history and culinary culture ‒ because it is there that Christmas reveals its most hedonistic and, let’s face it, most authentic side. During the Christmas period, eating becomes a liturgy that every culture interprets in its own way but which, ultimately, celebrates a primitive need: to satiate the body and, at the same time, the soul.

Bilton takes us back in time, exploring the history of the Christmas lunch and its emblematic dishes, from the Renaissance banquets of Christian Europe to the most unexpected rites: like the Japanese one, where KFC fried chicken has become, thanks to a brilliant advertising campaign, an essential Christmas dish, with kilometre-long queues already in November in front of the fast-food chain’s restaurants.

Of course, in some countries, like Italy, there are still those who dedicate themselves to the ritual of hand-decorated biscuits, of panettone prepared with a slowness that might appal contemporary humanity, always on the lookout for shortcuts.

But alongside these archaic rituals, some allegories of modernity also appear: sweets in elegant golden boxes as trophies of a standardized abundance. Roland Barthes, with his theory of modern myths, would probably have been fascinated by this transformation: the pre-packaged panettone as a simulacrum of Christmas, a symbol that has lost contact with its origins to become just a commodity.

But it’s not only food that defines Christmas. As The Christmas Book shows, Christmas is also songs, images, advertisements, films ‒ a whole constellation of references that, especially since the 20th century, have created a universal language of the holiday. The music listened to in this period is a true subculture, a phenomenon that continues to reinvent itself from generation to generation. And even advertising, with its saturated colours and idyllic scenes of happy families, has become an art in itself, a form of mass persuasion that reminds us every December how much we long for – or delude ourselves into thinking we long for – picture-postcard happiness.

The truth is, whether we like it or not, Christmas offers us a respite, a moment when we can all feel part of a group. The Christmas Book suggests that behind the sparkle lies a deep aspiration to share. As much as we are aware of the commercial traps, the clichés, in the end what matters is finding ourselves around a table set with old plates or adorned with fried chicken and paper napkins, to remember that belonging to someone or something – a country, people, your family or your own circle of friends – is the most precious gift. As Albert Camus wrote, “in the middle of winter, I discovered that there was, inside me, an invincible summer.” Maybe that’s what Christmas is: a little summer in the heart of winter, a light that warms us and which, for a moment, makes us all feel, simply, at home.

Antonio Mancinelli

BIO

Antonio Mancinelli, a professional journalist, was editor-in-chief of Marie Claire until July 2021. He collaborates with Repubblica, D ‒ La Repubblica delle Donne, Amica, Il Foglio and other online and offline newspapers. He started with Corriere della Sera. He teaches fashion journalism and fashion semiotics at various schools and universities. He has published several books: of these, the latest is L’arte dello styling (Vallardi) written in tandem with Susanna Ausoni, translated all over the world. Always conscious that fashion is a reflection of society and a political framework that can explain cultural changes, for years he has preached that everyone should dress how they want and not how they should. Nobody believes him.

Cover photo: The Christmas Book cover

Related products

Related Articles