Written by Vittorio Linfante, Simona Segre Reinach, Massimo Zanella and published by Marsilio Arte, “It’s Snowing! In art, fashion, design” guides readers on a journey of discovery of the sometimes-unexpected links between the imagery of snow and the many languages of creativity. Here is an excerpt from Massimo Zanella’s text included in the volume

Between snow and colors: when art depicts winter in motion

What happens when snow is not just a landscape, but a stage? When athletic movement becomes a visual narrative and the decorative arts are clothed in winter?

The relationship between art and winter sports has its roots in centuries-long depictions that talk to us about much more than simple pastimes: they speak to us of culture, of society, of aesthetics. The link between art and sport runs through the history of man as a finely drawn but fascinating thread. If painting has always sought to capture the movement and the emotion of athletic action, it is with the advent of winter sports in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that a new visual and conceptual chapter opened. But the story, in fact, began much earlier. In the Middle Ages, when organized sport was still a distant concept, we already find depictions that express the pleasure of play and competition on snow.

An extraordinary example of a medieval depiction of winter is to be seen on the frescoed walls of Torre Aquila, in the Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trento. Here, in around 1400, Maestro Venceslao created the famous Cycle of the Months, a masterpiece of International Gothic art that, with exquisite sensitivity, narrates the rhythms of the year and of human life. The month of January opens onto an enchanted landscape: snow covers the fields and hills, while in the background stands the castle of Stenico, at the time the residence of Prince–Bishop George of Liechtenstein. In the foreground, groups of nobles wrapped in elegant fur-trimmed cloaks challenge one another in a snowball fight, captured in a moment of collective, energetic play that is surprisingly modern. In the background, two hunters make their way through the snow accompanied by their dogs, while a fox and a badger move with caution among the trees, relating—almost by stealth—the silence of life in the snow-bound woods. The January fresco, with its wealth of detail and its skill in blending the courtly with nature and action, offers one of the earliest pictorial testimonies to winter life, not as an allegorical symbol but as a real, lived experience made up of movement, interaction, and connection with the environment.

Among the most fascinating examples of imagined medieval winters are the miniatures in the Très riches heures du duc de Berry, the legendary Book of Hours created in the early decades of the fifteenth century by the Limbourg brothers. The page dedicated to the month of February offers a vivid glimpse of a snow-covered landscape populated by figures immersed in the daily life of the cold season: peasants warming themselves by the fire, shepherds wrapped in cloaks. The movements and gestural expressiveness of the figures convey an idea of winter as an active, social time, a time of sharing. With the wealth and variety of their decoration and meticulous attention to detail, the Très riches heures offer one of the first figurative representations of winter, anticipating— with courtly elegance—the dialogue between the body and its environment that would return, centuries later, in the paintings of the great artists of northern Europe.

With the arrival of the modern age, between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, interest in winter landscapes became more systematic, especially in Dutch and Flemish art. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, with works such as Hunters in the Snow (1565), paved the way for a new sensibility. The center of the painting is occupied by three hunters who, together with their hounds, are returning to the village after what was probably an unsuccessful hunt; but it is in the background, which opens as if a theater curtain beyond the hill, that the painting reveals all its narrative wealth: a frozen expanse on which tiny figures move about, engaged in various activities on ice and snow—men skating, children sliding, women carrying bundles of wood, others playing games, diving, falling. A swarm of gesticulations, efforts at maintaining one’s balance, of physical encounters and sociability, in which a surprising variety of movements, rhythms, and postures appear. This is not yet sport in the modern sense of the word— there is no codified competitive element—but clearly there are forms of shared physical activity in a communal winter space.

During the seventeenth century, Dutch painting in fact developed a new perspective on the cold season. One of the most outstanding masters who made winter a central subject of their work is Hendrick Avercamp, an attentive and meticulous artist, with the skill to transform ice into a crowded stage teeming with life. In his paintings, frozen canals and lakes become the beating heart of the Dutch winter: men, women, and children move around engaged in skating, trading, playing, falling over, and loving. Snow and ice are not just atmospheric elements, but true narrative agents able to convey the rhythm of cold, festive days. With his ironic gaze and taste for detail, Avercamp captures a world in which everyday gestures become part of a choral narrative, making the winter landscape an autonomous, identifiable genre, deeply rooted in city life and its inhabitants.6 Winter thus becomes a lived, shared space, observed with a modern eye, able to depict and recount the relationship between body, nature, and society.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Impressionists also made a fundamental contribution to the evolution of the artist’s view of winter. For them, snow was no longer simply a narrative backdrop or a seasonal allegory, but a luminous, vibrant, continually changing material. Artists such as Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Camille Pissarro painted snowy landscapes with light brushstrokes and cool colors, paying close attention to atmospheric effects, nuances of light, and variations in tonalities of white. In their paintings, snow becomes a sensory experience, a field of unalloyed observation.

What has changed is the modernity of their gaze: winter is no longer represented as a constructed scene, but as a visual impression, as a phenomenon that envelops, distorts,

and transforms. And even though sporting scenes rarely make an appearance, it is precisely this new attention to light, atmosphere, and movement that paves the way for a more dynamic and suggestive representation of the winter environment, anticipating sensibilities that will develop in full in the twentieth century.

[…]

SPORT, ELITE AND ILLUSTRATED IMAGERY

With the beginning of the twentieth century, winter sports ceased to be merely a physical activity: they became a lifestyle. The earliest Alpine resorts—Saint-Moritz, Davos, Chamonix, Cortina d’Ampezzo—were transformed from quiet mountain villages into elite destinations frequented by aristocrats, entrepreneurs, and artists, the mountains elegantly decked and winter clad with glamour.

This cultural transformation was also reflected in the visual arts, particularly in advertising graphics. Between the 1920s and 1930s, illustrators such as Emil Cardinaux and Erich Hermès created promotional campaigns for the new Alpine ski resorts, transforming the sport into an aesthetic and commercial phenomenon. The snow-covered landscapes no longer depict nature or athletic exploits but become the icons of a sophisticated lifestyle, made up of imposing hotels, impeccable slopes, fashionable techwear, and elegant social occasions.

Emblematic in this sense is the work of Tamara de Lempicka who, in her painting Saint-Moritz (1929), depicts a woman skier with a geometric face and a proud gaze: an autonomous, elegant, modern figure, a true style icon, embodying the image of the chic, athletic woman, perfectly at ease in speed as in alpine glamour.

Among the most original and intense visions of winter in early twentieth-century painting is that of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, a central figure of German Expressionism and co-founder of the Die Brücke group. Kirchner’s vision of winter is neither nostalgic nor descriptive in spirit: His gaze is restless, modern, and tense. In the painting Skating Scene (c. 1920), the ice is not simply a backdrop but a psychological field: bodies move along forced diagonal lines, poses are tense, faces simplified, and athletic movements become reflections on identity, speed, and solitude.

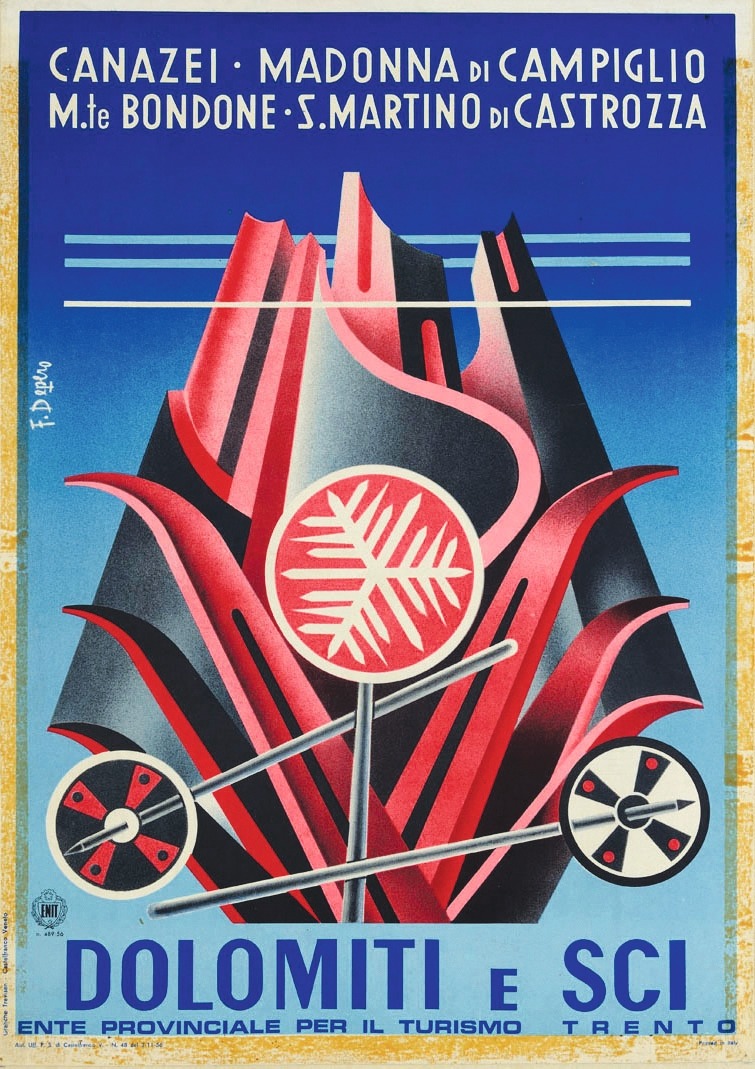

Fortunato Depero, a native of the Trento area and deeply attached to it, interpreted the subjects of speed, strength, and dynamism within a coherent and personal vision. In his works, skis, mountains, and equipment become elements of a visual language made up of fragmented shapes and vibrant colors, where everything is momentum and rhythm, as in Montagna con sci e piccozza (Mountain with skis and ice ax, 1930–1940), a small oil painting in which the peaks are transformed into live geometric structures. However, it was in the 1950s that he produced some of his most accomplished works. Between 1953 and 1956, he designed the so-called Sala Depero in the Palazzo della Provincia Autonoma di Trento, a “total” environment where walls, furnishings, and decorations come together to construct a colorful and dynamic world. Although it was one of his last works, it retains all the visionary energy of optimism, vitality, and invention. In 1956, he also designed the poster Faites du ski dans les Dolomites, in which skiing becomes acrobatic, stylized, and light. The figures, cut out as though angular collages, merge with a mountain that evokes both the peaks, and the soaring architecture dear to the Futurists. For Depero, sport was a way of narrating modernity.

In the meantime, specialized publishing grew and in Italy magazines such as Lo sport fascista, La donna, and Le vie d’Italia celebrated snow with illustrated articles that mixed propaganda with modernist imagery. In France, Adam, La Mode chic, and Sports d’hiver dictated the style

of holidays in the mountains. In Poland and the United States, publications such as Zima, Sport Zimowy, and The Illustrated Sporting News portrayed skiing as a discipline and a social ritual. Between glossy photographs and stylized drawings, athletic bodies—both male and female—were sculpted into heroic and dynamic poses, consistent with the aesthetics of the time.

While illustrations were a guide to style and behavior for adults, children also had their own snow-clad fantasies, made up of magazines and picture books featuring stories set in the snow, sleigh rides, skiing puppets, and playful sports alphabets. A famous example is A Winter Sports Alphabet (1926), illustrated by Joyce Dennys with ironic texts by “Evoe” (E.V. Knox): a snobbish and amusing alphabet that recounts the vices and virtues of alpine life. In Italy, Antonio Rubino, leading illustrator for the Corriere dei piccoli, created a poetic universe where snow is play, land of dreams, and stories. Children on sledges, anthropomorphic animals, snowball fights, and Art Nouveau figures populate pages filled with rhythm and imagination. With his decorative and dreamlike style, Rubino transforms athletic movement into visual poetry. His illustrations, often accompanied by rhymes, become bridges connecting play, art, and education. His work extended well beyond the page: many of his images would inspire toys, paper theaters, and cut-out silhouettes. In an era when toys reflected cultural change, winter sports entered children’s bedrooms. Made of wood, tin, or papier-mâché, small spring-loaded skiers, sledges, and rocking skaters flooded the European market—Germany, Austria, France, and also northern Italy.In the 1920s and 1930s, with the boom in middle-class Alpine tourism, winter toys also took on aspects relating to identity and education, with companies such as Lehmann, Fernand Martin, and INGAP producing bobsleighs, ski puppets, and snow-covered theaters. In the 1940s, Kay Bojesen in Denmark created Boje and Datti, two renowned wooden skiers inspired by his own family members.

With the arrival of Barbie, skiing definitively entered the global pop imagination. On the slopes since the 1960s, Barbie, together with Ken, Skipper, and the whole extended family, embodied an idea of sport and femininity that constantly evolved in line with fashion, technology, and aesthetic tastes. An artful mix of plastic, color, and performance, Barbie became a visual narrative, in perfect harmony with the pop language that, in those very years, was beginning to redefine the boundaries between art, consumption, and mass culture. […]

Massimo Zanella

The text is taken from da It’s Snowing! In art, fashion, design, Marsilio Arte, Venice 2025

BIO

Massimo Zanella is an art historian and iconographer with a passion for music, literature, art and fashion. Alongside these interests, he works as a book designer and editor for some of Italy’s leading publishing houses. He is the author of essays on art and fashion history and illustrated books, including Il design del tessuto italiano (Marsilio Arte, 2023).

Captions:

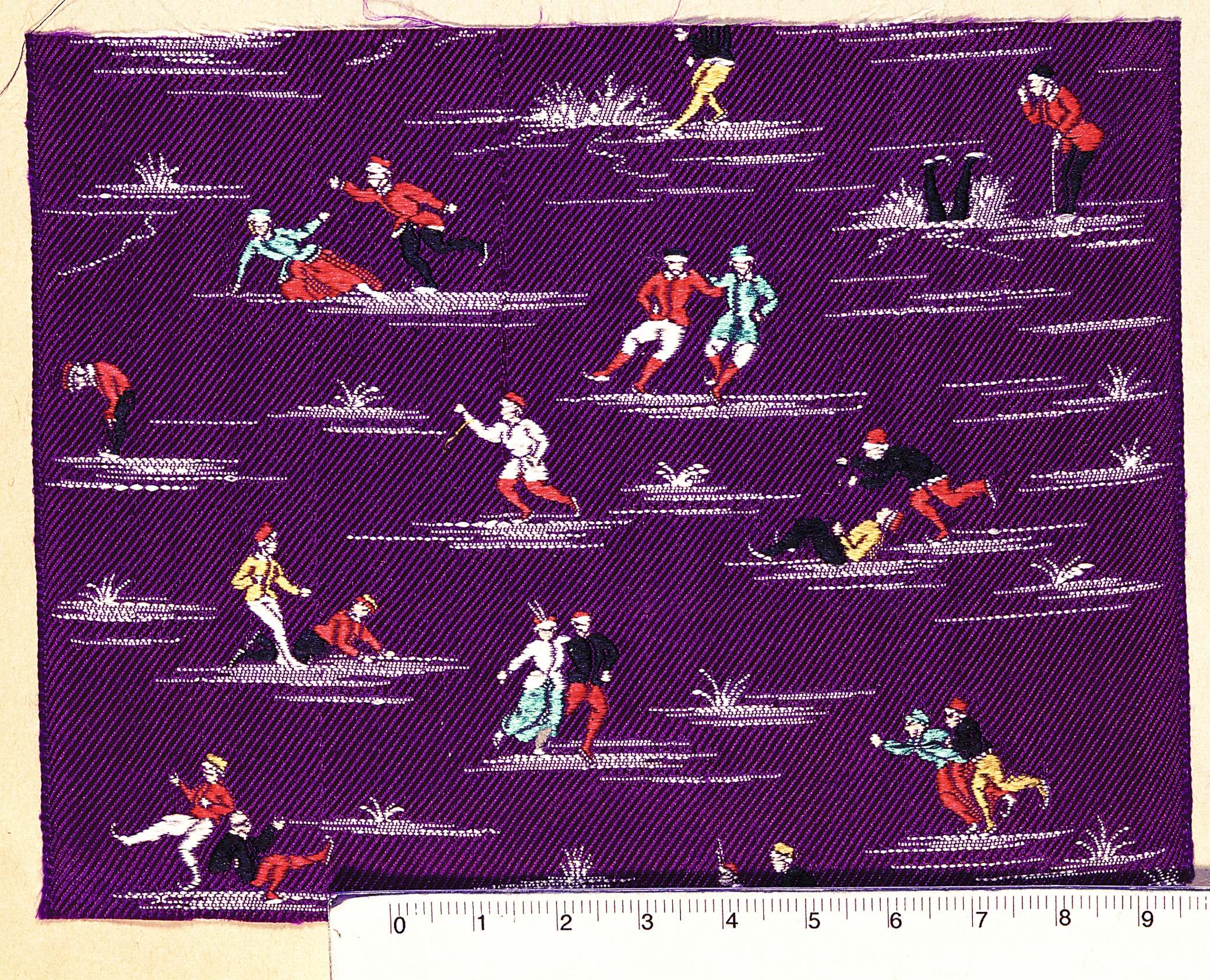

French manufacture, Winter sports, 1880-1890. Brocade, Como, Fondazione Antonio Ratti. Page 29 of the volume

Fortunato Depero, Dolomites and Skiing, 1956. Colour lithograph on paper, private collection. Page 62 of the volume

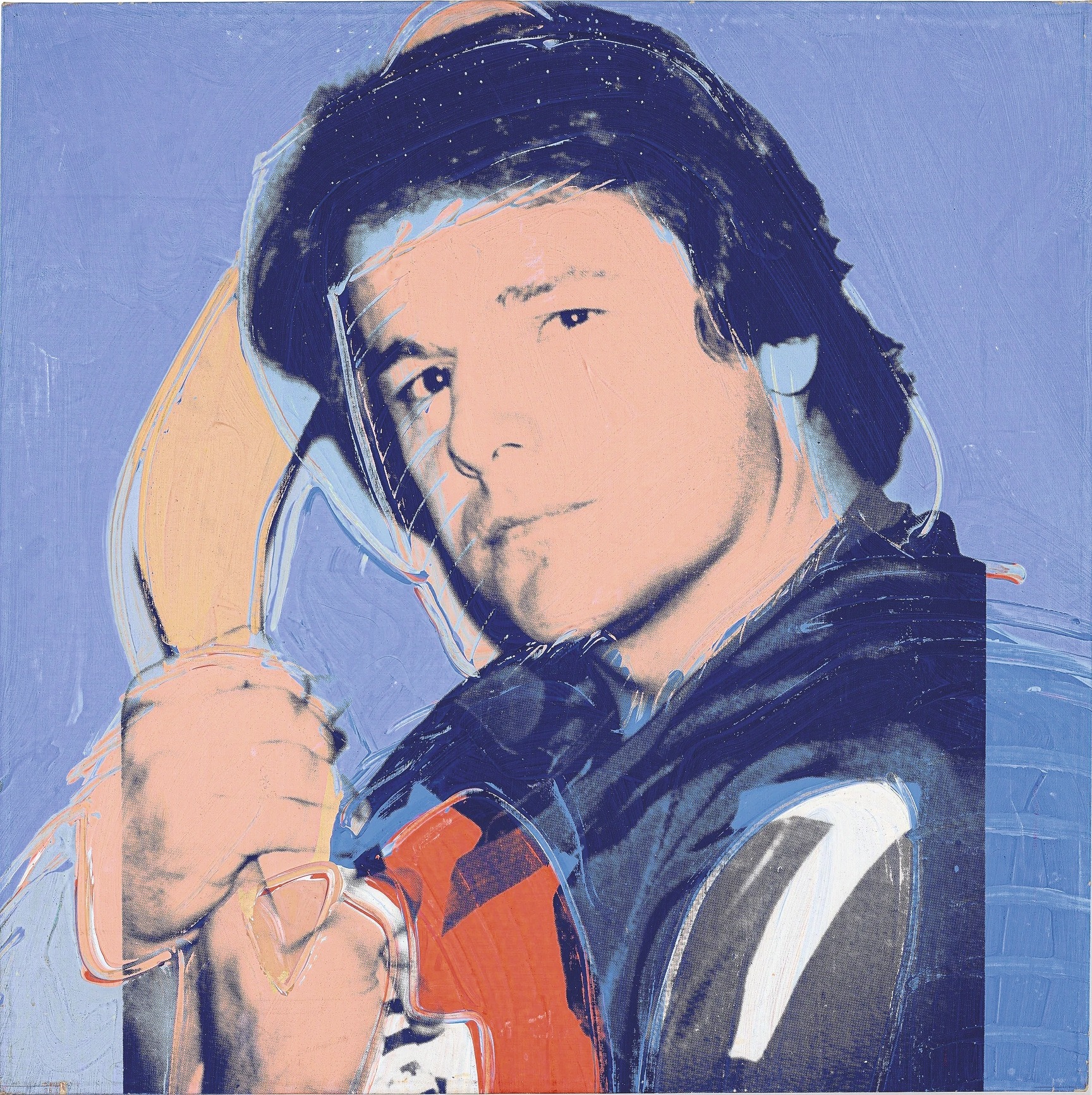

Andy Warhol, Rod Gilbert, 1977. Colour silkscreen print on canvas, private collection. Page 62 of the volume

Elena Scavini x Manifattura Lenci, Turin, Skier, circa 1930. Earthenware, Rosignano Maritimo, Raffaello Pernici Collection – Best Ceramics. Page 73 of the volume

Gio Ponti X Società Ceramica Richard-Ginori, Doccia, Six plates from the series “Gli Sport”, circa 1930. Porcelain, private collection. Page 86 of the volume

Gerhard Riebicke, Waiters on skates serve drinks to guests on the ice rink of the Grand Hotel in St. Moritz, circa 1925. Black and white print on paper, private collection. Page 88 of the volume

Moncler, advertising campaign, 1982. Colour print on paper, private collection. Page 146 of the volume

Gladys Perint Palmer, Illustrations for the Missoni Women’s Collection, 1992. Markers on paper, Missoni Archive. Page 193 of the volume (cover photo)

Riccardo Guasco x Esselunga, Slalom, 2025. Courtesy Riccardo Guasco. Page 230 of the volume

Related products

Related Articles